Orthopedic specialists look to control pain without dangerous drugs

Naperville resident Steve Bruebach found himself in a quandary as he prepared for a double hip-replacement surgery in August 2020. Typically, Bruebach doesn’t like to take medication unless it’s absolutely required. But a medical technician warned him: Don’t wait until you start hurting to take medication for pain, because you’ll be playing catch-up, and that’s hard to do.

Still, Bruebach recalled the son of a client who became addicted to opioids prescribed to him following an accident at work. Bruebach decided to take the opioid Norco, as prescribed by his doctor, for the first 24 hours post-surgery, and ween himself off the next couple of days by waiting longer intervals between doses and taking Tylenol as needed.

Bruebach’s plan worked. Within two days, he stopped takingall medications. “I had discomfort, never pain,” he says. “I could still function, so I wasn’t going to medicate myself.”

Turns out, his instincts were spot-on.

“Studies show the vast majority of patients do not require opioids long-term after surgery. If at all, two to three days at most,” says Brian Clay, MD, physiatrist and pain medicine specialist with Illinois Bone & Joint Institute.

A study published in June 2021 in the Annals of Surgery concluded that treating postsurgical pain with nonopioid medications, such as ibuprofen or acetaminophen, didn’t lead to patients suffering from higher pain levels or more serious issues.

The study examined results from 22,000 patients who had hernia, gallbladder, appendix, bowel, thyroid, or gynecological operations and found that the patients who were not prescribed opioids after surgery had similar outcomes as those who were prescribed opioids.

Risky use

For decades, doctors have routinely prescribed opioids to manage postsurgical pain. But opioids have addictive potential that can lead to persistent use.

In fact, Purdue Pharma, producer of OxyContin, has been tied up in lawsuits for years because government officials allege the company knew the drug was highly addictive but pushed sales to maximize profits.

The movement toward nonopioid medications grew in 2017 and 2018, when doctors began to see massive increases in both opioid prescriptions and opioid-related deaths, says Clay, noting the street drugs heroin and manufactured fentanyl are also classified as opioids.

Studies show the vast majority of patients do not require opioids long-term after surgery.”

“You have crossover between the medical community’s desire to manage pain with a much broader societal problem — drug abuse. And the drug happens to be an opioid responsible for increasing deaths in the U.S. in the past decade,” Clay says.

But that’s not the only downside of opioids, according to Clay. Some people suffer severe side effects: constipation, nausea, vomiting, itching, lethargy, and brain fog.

There is also a risk of accidental overdose, either from miscounting the dosage or taking more than prescribed, as well as respiratory depression, which occurs when elevated levels of opioids slow the breath rate by blocking receptors in the brain that control breathing. This can lead to death by asphyxiation.

Enter the alternatives

Opioids are actually short-acting medications that don’t do a lot to target inflammation, which is a root cause of pain, says Ravi Bashyal, MD, an orthopedic surgeon at NorthShore Orthopaedic & Spine Institute in Skokie.

“Inflammation is the reason an arthritic hip or knee hurts because cartilage is worn out or bones are rubbing together, which starts inflammation and causes the body to send a signal to the brain that something is going on here, send some blood and swelling to help calm it down.”

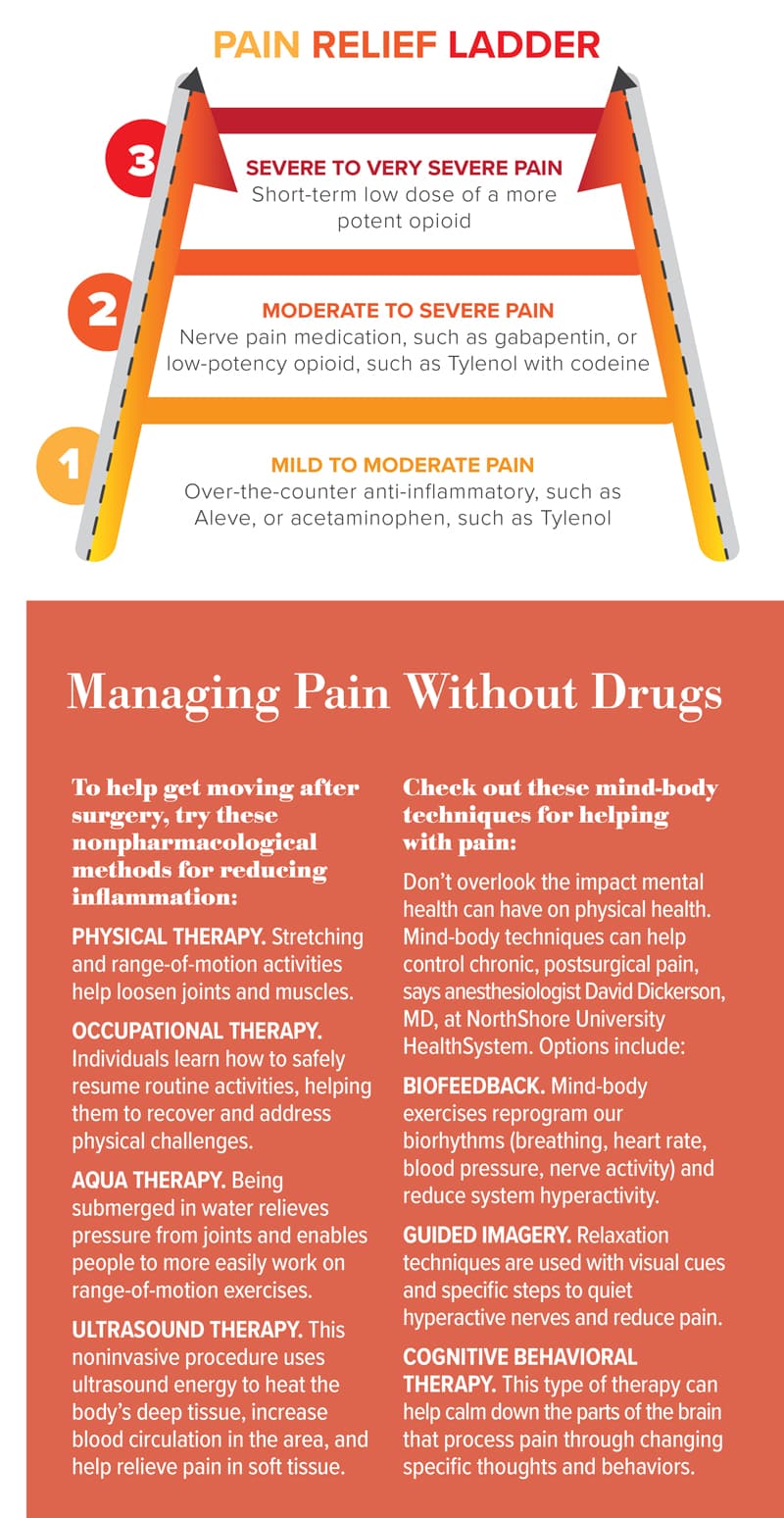

Bashyal and his team perform minimally invasive, outpatient hip and knee replacement surgeries using a spinal anesthetic to block nerves. To manage postoperative pain, he gives them a combination of opioid-free medications from the WHO’s analgesic ladder.

This approach works, Bashyal says, because technology enables more efficient surgeries. Minimally invasive surgical techniques decrease the body’s inflammatory response and people’s pain, he says.

“In the past, hip or knee replacement surgery required a postoperative three- or four-night stay at the hospital, one to two weeks in a nursing home, a month of using a cane, and a prescription for two opioid medications,” Bashyal says. “Now, patients have surgery in the morning, go home in the afternoon, and never use opioids in recovery.”

Movement as medicine

Yet, anesthesiologist David Dickerson, MD, section chief for pain medicine at NorthShore University HealthSystem, emphasizes that people shouldn’t feel bad if they require opioids to treat acute pain following surgery in order to move, because movement is vital to recovery.

“Movement improves patients’ pain tolerance and prevents musculoskeletal issues — muscle spasms or arthritis — that can worsen pain and function,” Dickerson says. “Early mobilization has been shown to improve the recovery and range of motion of the recently operated-on part of the body.”

As part of his recovery process, Bruebach participated in six to eight weeks of physical therapy. During his recovery, he says he only experienced discomfort, not pain.

But Bruebach says his doctor never discussed opioid-free options with him. Taking Tylenol instead of the opioid Norco was his own idea, he says. Nonetheless, he admits he is not prone to drug dependence. “I’m fortunate,” he says. “I don’t have that urge to keep taking them.”

Unfortunately, many people are prone to dependence. Opioid-free options reduce that risk.

Originally published in the Fall/Winter 2021 print issue.

Melanie Kalmar is a journalist specializing in business, healthcare, human interest, and real estate. When not writing, she enjoys spending time with family.