Supporting youth to be their true selves

You think of Caitlyn Jenner in a white corset on the cover of Vanity Fair or Laverne Cox’s struggles with one of her on-screen inmates in the Netflix hit series Orange Is the New Black.

The problem is that the vast majority of Americans do not personally know, or think they know, anyone who is transgender. What is most definitely true (and also widely misunderstood) are these facts:

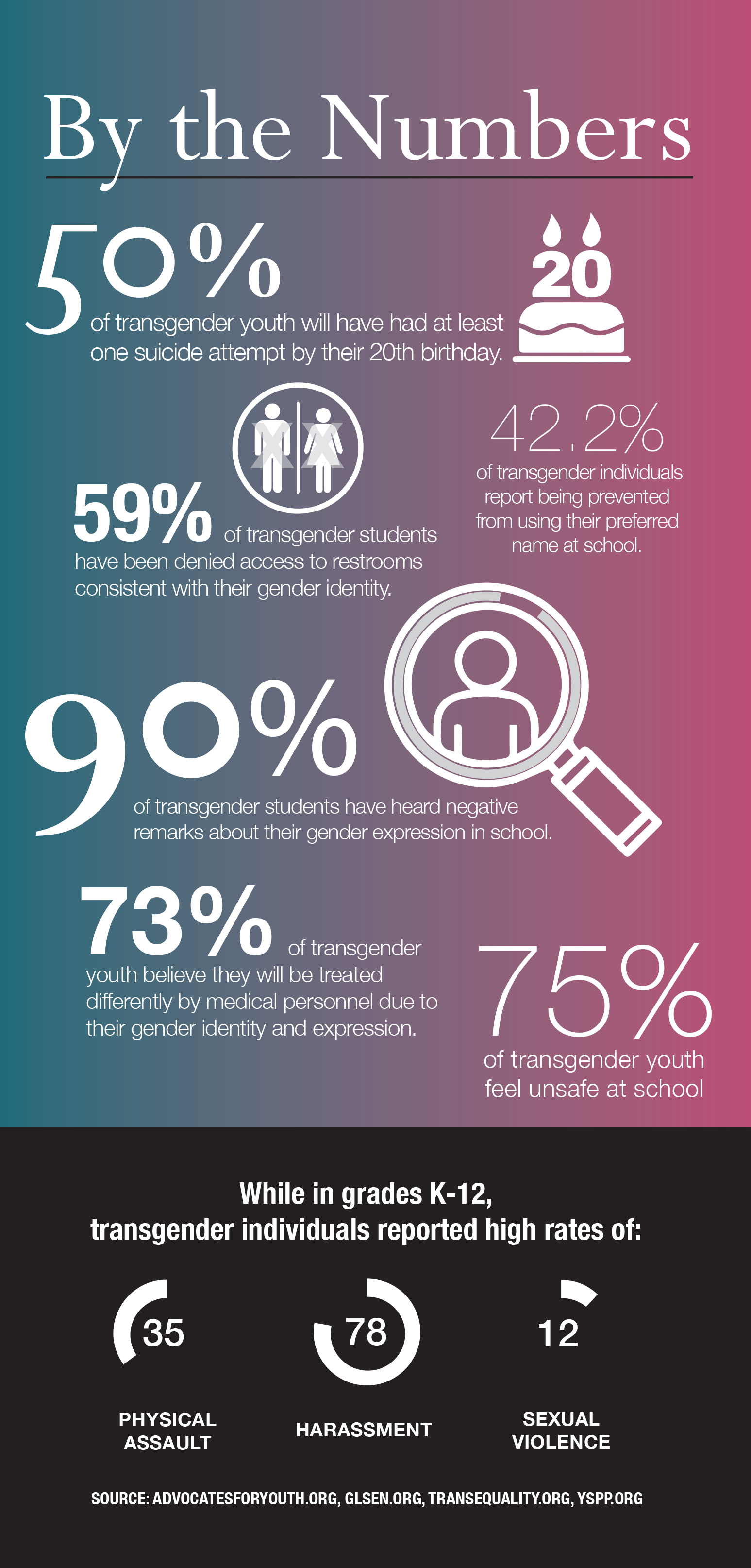

Forty-one percent of transgender persons attempt suicide at some point in their lives.

Almost half (44 percent) of transgender students reported that they had been physically assaulted at school in the past year, according to the Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network.

Transgender isn’t something you can catch. It doesn’t require a cure, and it’s not a phase.

Gender identity isn’t the same as sexual orientation; meaning that transgender people may be straight, gay, lesbian, bisexual or asexual, just the same as nontransgender people.

Growing up is difficult enough when you’re totally on board with the biology you’ve been dealt. Now imagine being at odds with your gender.

With strong social role models appearing, more youth are feeling permission to openly explore gender. And here in Illinois, we’re graced with a supportive and deep medical and advocacy community to guide transgender youth on their already difficult journey to adulthood.

The Problem of Vocabulary

The Problem of Vocabulary

“Imagine waking up every day and looking in the mirror and feeling an unmanageable amount of distress and panic, as everything you see—from the clothes your parents dress you in, to the bathroom you’re told to use, to the toys your parents have given you over the holidays, to your name—[does not] match how you feel as a person,” says Brandon Hill, PhD, executive director of the Center for Interdisciplinary Inquiry and Innovation in Sexual and Reproductive Health at the University of Chicago.

What Hill describes is called gender dysphoria. In plain English, this means that a person’s emotional and psychological gender identity do not align with the biological sex at birth and causes an unmanageable amount of discomfort. A person may look like a boy but feel like a girl (or vice versa).

At birth, children have no sense of gender. Gender roles are something they learn from their environment as early as age 3. While the medical community agrees that it is impossible to definitively know how a child with gender issues may identify when they are older, it is important for parents to recognize when their child’s birth gender is causing them anguish and distress. Supporting who they are without making assumptions and decisions for them is important for all youths, regardless of whether they identify as gay, lesbian and/or transgender in the future.

The Power of Supportive Parents

While each young person’s journey is different, one thing that’s inarguable is the importance of family support.

“With love, support and acceptance, kids just do better,” says Scott Leibowitz, MD, head child and adolescent psychiatrist at the Gender and Sex Development Program at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago. As Leibowitz works with youths and their families—who come for support from across the state—he knows that parents are integral to a child’s or adolescent’s journey.

“Gender dysphoria is a family issue. Part of my job is helping everyone in the family process the experience at their own pace,” Leibowitz explains. “I’m there to validate everyone’s experience and let them know it’s OK to be where they’re at with the issue. Everyone in the family is entitled to have a reaction to what’s going on.”

The time for families to seek assistance is when a child’s happiness and ability to function is compromised because of a potential gender identity issue. A child’s distress might intensify just prior to or during puberty. Puberty brings on irreversible changes to a child’s body, which for transgender adolescents can evoke a highly negative and powerful experience that needs to be addressed.

On that note, Leibowitz reinforces his role in helping transgender youth see their whole selves. “Youth experiencing gender dysphoria can feel that they see the world only through that lens; that it’s all-encompassing of who they are. Society often reinforces that, and people tend to make assumptions about transgender people. Actually, being transgender is only one component of their identity. It’s not the only lens they have.”

As transgender youth grow older, medical confirmation of gender becomes a possibility. While not every transgender person chooses transition, it’s important to know how medical science is easing the journey for transgender youth and their families.

Physical Gender Confirmation

Loren Schechter, MD, leads the Center for Gender Confirmation Surgery at Weiss Memorial Hospital. He’s also an advocate for referring to surgical intervention as gender confirmation surgery instead of “sex change operation” or “sex reassignment surgery.”

“I perform surgery that allows someone’s physical persona to be consistent with who they know themselves to be,” he says.

Patients under the age of 18 make up roughly 10 to 15 percent of his practice. The majority are transgender men (natal females confirming as male). His youngest chest surgery (removal of breast tissue) was on a 14-year-old patient, and his youngest vaginoplasty (natal male confirming as female) was 17.

But prior to surgery, what’s the journey?

Schechter says there are always multiple professionals involved with each of his adolescent transgender patients. From psychology to advocacy, it’s a comprehensive journey. “Adolescence is hard enough. When you add in gender dysphoria, it’s even harder. I’m here to ease that journey,” he says.

One of the most prominent advances in care for transgender youth has been the introduction of the pubertal blockade, he says. Pioneered in the Netherlands, pubertal blockades are hormonal treatments that prevent the development of secondary sex characteristics associated with puberty such as breast development, Adam’s apples and jawline definition. This allows adolescent patients to thoroughly explore their gender identity without the progression of irreversible effects brought on by puberty. Pubertal blockades are fully reversible; meaning adolescent patients who recognize that they do identify as their birth gender can end the treatment and experience puberty by allowing the body’s natural hormones to take over.

Timing is a key concern, as confirmation surgeries are commonly planned at transitional phases of a person’s life such as between high school and college or a significant move/relocation. Young transgender people often want to start a new phase of their lives being comfortable with who they are, inside and out.

Support Meets Shortcomings

When you get Jennifer Leininger, MEd, program coordinator for Lurie Children’s Gender and Sex Development Program, on the phone, there’s an unmistakable professionalism and enthusiasm in her voice. For more than eight years, she’s worked with LGBT youth and families, from being an advocate for gender-inclusive bathrooms at Lurie Children’s and Chicago Children’s Museum, to meeting regularly with school administrators across Illinois, to coordinating support groups for transgender youth.

“When meeting with organizations and schools, my goal isn’t to change hearts and minds, but to give everyone the tools to make a child feel as comfortable as possible,” Leininger says. Her job is to connect people with resources to assist the transgender community, from legal name changes for transgender youth to training and development protocols for teachers and school administrators.

With program participants at Lurie driving as much as two hours each way just to attend social support groups for youth and adolescents, it is clearly evident that the role she plays is essential in creating a supportive environment for them.

But while psychological and medical support for transgender youth have increased significantly in the past few years, the world at large is still vastly ill-equipped, in both policy and understanding, to create a truly welcoming environment for the transgender community, Hill says.

“As a country, we’re far behind in policies that support and protect transgender people,” says Hill, who researches systems and societal structures that influence mental and physical health for transgender, gender-nonconforming and LGB adolescents.

“In several states, employers can discriminate—without legal recourse—against transgender persons. In most schools, children can still be forced to use the bathroom of [their birth] sex instead of the gender they identify with. Until state and federal policy catch up in structural support and legally protect transgender individuals, we won’t necessarily see broader changes in health.”

While medicine can bring transgender youth to a point of physical and emotional equity, society has a long way to go to make this vastly underserved population feel accepted—and most importantly—protected, he says.

What’s Next for Transgender Youth?

The key to positive outcomes is to provide transgender youth a safe and supportive environment for their journey. Inclusion is of the utmost importance since one of the leading indicators for transgender youth who have negative outcomes (suicide or self-harm attempts) is the feeling that they don’t belong and have no one sympathetic to their experiences.

With a bit of love and listening, parents can help children access the medical and psychological resources that can support a transgender youth’s journey. Through advocacy, all persons affected by a youth’s journey through transgender identity development and transition—educators, families, coaches, friends, neighbors and the medical community—can demand better protections and accommodations for those whose journey with gender is vastly different and perhaps more complex than many of us will ever know.

Originally published in the Spring 2016 print edition.

E. Napoletano is an award-winning author and journalist. Curiosity leads her to her greatest adventures and stories.