Englewood’s Go Green Fresh Market reimagines food security and prioritizes community engagement

At the corner of South Racine and 63rd Streets, just down the street from a boarded-up CTA green line station, Go Green Community Fresh Market has changed what it means to be a convenience store. Fresh Market replaces traditional convenience store items, such as soda and candy, with fresh produce, made-to-order meals, and other healthy living necessities.

Located at 1207 W. 63rd St., the store stands to make a huge impact. It opened in March 2022, in Englewood — a notorious food desert, where at least one-third of residents live more than a mile from access to fresh produce and other healthy foods. The store is within walking distance for 6,000 residents, who spend as much as $55 million on groceries outside of their own community every year, according to the Go Green on Racine project.

“This is an upscale community corner store. It’s a corner store with options that aren’t just nachos. It’s going to be a better meal for you and your family,” says Fresh Market head cashier Fabia Garner.

Multiple community groups came together under the Go Green on Racine name to make the Fresh Market a reality. The Inner-city Muslim Action Network (IMAN) runs the Fresh Market, but E.G. Woode, Residents Association of Greater Englewood (RAGE), and Teamwork Englewood all worked on the nearly $5 million Fresh Market — the first in a series of projects under the umbrella of Go Green on Racine.

The multi-million dollar Go Green on Racine project, which will play out in three phases, prioritizes holistic, regenerative, community health. Fresh Market specifically had funding from Chicago’s Neighborhood Opportunity Fund, The Kresge Foundation, The Builder’s Initiative, The Walton Family Foundation, and Self-Help Ventures Fund.

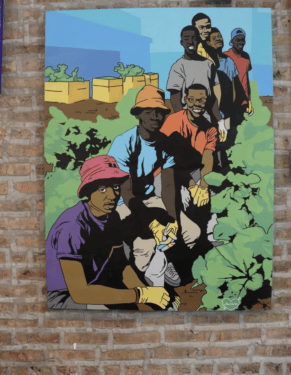

The store sells everyday household items and cleaning products, as well as organic soups, cereals, vegan options, and fresh produce. Bright and welcoming, community artwork decorates the space.

Creating access

Local neighborhood groups, including IMAN, have been focused on Englewood’s food desert emergency for years, but they’re up against decades of racism as well as abandonment from the city and investors. When Whole Foods opened in the neighborhood in 2016, shoppers lined up to celebrate long-awaited fresh food options. Six years later, as Fresh Market opened its doors, Whole Foods announced it would close. In a May news conference, Mayor Lori Lightfoot called the closure “a gut blow” to Englewood.

Darren Jeters, former Fresh Market manager, acknowledges that Whole Foods leaving has its pros and cons for Fresh Market and Englewood.

“Although it may be somewhat beneficial for us in a business sense, as a whole, we are trying to give this area access to food,” Jeters says. “Losing one institution is a detriment to that plan. Hopefully, that space gets transformed into another food entity. This community desperately needs as many food resources as possible.”

Englewood is 92% Black, and 55% of residents make less than $25,000 annually, according to the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning (CMAP). Jeters hopes the market diversifies people’s diets, helping to mitigate health risks and lead to longer lives.

“We try to bring in things that people aren’t familiar with. We are trying to revamp the conventional diet,” Jeters says. “The urban diet is very convenience-focused. When you eat [processed foods], you get a lot of high cholesterol, high sodium, and high sugar. In the long run, these things chop off years at the end of your life. We’re trying to give people an alternative to help close the health disparity gap.”

And it’s a huge gap. Statistically, Englewood residents live 20 years less than residents of Chicago’s downtown neighborhoods, according to data from the City Health Dashboard.

Ed Stellon, executive director of Heartland Alliance, which has a health center in Englewood, says the food on people’s plates plays a major role in that gap. “Heart disease, hypertension, lipidemia, high cholesterol, and diabetes are diet-driven diseases,” Stellon says. “The absence of healthy food on our dinner plates is a bigger issue than the presence of ultra-processed food.”

Fresh Market challenges the typical convenience store selections and creates what Stellon calls essential access. And the market takes another key step as well: connecting with community through education and events. In store and on Instagram they promote community barbecues, guest speakers focused on grassroots power and music, and healthy eating workshops with dietitians.

Local focus

Fresh Market empowers local vendors and labels products with BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color) stickers when applicable, to highlight BIPOC suppliers. IMAN Project Manager Sharon Hoyer says the organization works with a couple dozen hyper-local vendors, and almost 20 of them are Black-owned or based in Chicago.

Abdul Rahman, community engagement and safety personnel officer, says that his role is more than security. “Our first goal is to engage with the community so people know about these programs, then provide a safe environment,” Rahman says.

For many Englewood residents, getting to the Fresh Market takes a short drive or walk. The CTA green line isn’t available, despite a stop just next to the store. In the early 1990s the city closed the Racine train stop, and IMAN and other advocates are advocating to get it reopened.

“Advocating for reopening the Racine station had momentum last year, and that was quite successful. We’re seeing the higher-ups say, ‘We’re interested in this.’ Now we want to make sure there is community buy-in. We’re in the phase of moving into petitioning in the community,” Hoyer says.

There are also plans to add parking spaces in the vacant lot beside the store. “The lot will likely have seven car parking spaces and include a pedestrian plaza. There is a plan for planting trees around the perimeter and a mural on the wall. The community wants to see the space activated with dance, so there will be a stage,” Hoyer says.

Further plans within the Go Green on Racine project include housing, green jobs training, and continued partnership with local food growers and makers.

Rahman acknowledges that the store and Go Green on Racine have a long way to go. “Every 1,000-mile journey begins with one step, and I guess we’re 200 steps in,” he says.

Kala is an environmental journalist passionate about climate change mitigation and environmental justice. Kala writes about regenerative food systems, endangered species, and urban forestry. She is currently earning her Masters in Journalism at Northwestern.