A Q&A with investigative journalist Jordan Chariton, author of We the Poisoned, on the significance of lead and protecting the Great Lakes Water Basin

Fact checked by Catherine Gianaro

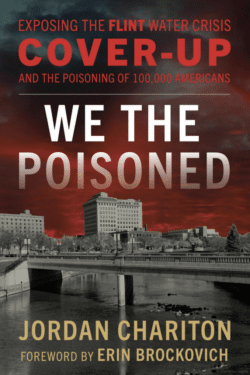

The Flint water crisis first unfolded more than a decade ago, but as journalist and author Jordan Chariton recounts in his new book, We the Poisoned: Exposing the Flint Water Crisis Cover-Up and the Poisoning of 100,000 Americans, the city’s water system remains compromised. And so does residents’ health.

In the book, Chariton argues that rather than incompetent agencies or environmental racism, the decisions that led to Flint’s poisoned water were part of a deliberate scheme to funnel Great Lakes water — which makes up more than 20% of the world’s fresh surface water — for private industry and profit, particularly for oil fracking. I spoke with Chariton recently to understand the bigger picture of how what happened in Flint impacts the rest of the Great Lakes watershed, including the Chicago area.

Jordan Chariton: If you listened to the state of Michigan or the EPA [Environmental Protection Agency], they’ll say it’s fine. The media narrative that Flint is recovering is not true. Ten years later there are still water problems. Residents are still showing me rashes and still showing me pictures of brown water. It’s not as bad as it was, but it’s still, in many parts of the city, smelly and discolored water. [This] makes sense, because 10 years later, they have not fully replaced all of the damaged pipes. Technically water is coming through the city of Detroit, not the Flint River, but there’s still major problems because the pipes have not been replaced.

CH: The way you describe Flint — a once-prosperous, mid-sized city where the majority of the population belongs to a racial minority — sounds a lot like Gary, Indiana. To the best of your knowledge, how does Flint’s situation compare to past water and health issues along Lake Michigan’s south shore?

JC: What happened in Flint has happened before and can happen in any city with major population decline. (Flint’s water system was designed for 200,000 residents, it now has around 80,000). Any place with abandoned homes or things like that, with a water system too big for its current size. Water will move too slowly through (the system). Chemicals added to the water like chlorine get absorbed too quickly because the water isn’t moving. Between the [outdated] pipes and stagnant water, you’re going to have big problems.

CH: What kinds of reporting on this issue have you done in other Lake Michigan towns?

JC: I covered the East Chicago, Indiana lead issues years ago. East Chicago basically built a government housing project on top of a lead smelting plant. What did they think was going to happen? I went to East Chicago in 2016, and I couldn’t breathe; the soil was so contaminated. We have a major problem in this country with corporate pollution. Whether it’s East Chicago, or Gary, or so many other areas, where you have legacy corporations, government officials look the other way on environmental health. Corporations aren’t intentionally poisoning waterways, but it’s through waterways that their waste process leaks.

CH: How did your experience with East Chicago compare to the coverage of Flint?

JC: It’s funny, I remember in East Chicago there was an EPA [Environmental Protection Agency] trailer, the guy there kept telling me, “This is not Flint! There’s no (comparable) water issue here!” But I kept hearing from residents that there was a water issue, with high lead levels. It’s the same thing: Either government actors are deliberately misleading, or they are very wrong. The major difference with Flint was the reckless, acute decision to switch water sources. Whereas in East Chicago, those are generational problems that build up over time. The contamination grows, accumulates over decades, really. People get sick, but we’re talking about the difference between people developing illness over decades vs. six months. It’s similar, and sometimes harder to pinpoint: How many people got cancer from lead poisoning, but it was never properly attributed to that? Communities in East Chicago or Indiana, researchers have shown high levels of asthma, bronchitis — that’s all from this corroded infrastructure.

CH: How concerned are you about America’s water infrastructure overall?

JC: I don’t want to scare anyone, but the truth is that the greatest national security threat is our water supply. Contaminated water is going to get you sick and shorten your life span. Lead is a serious problem. The EPA is finally starting to regulate PFAS, which are being found everywhere. Politicians and the media treat this issue like something we can chip away at, address over time. I think our water system is an urgent emergency. Why aren’t we doing a New Deal-type program to retrofit systems, fix water systems?

(Editorial note: On Oct. 8, a week after my conversation with Chariton, the EPA issued new rules to phase out lead pipes across America within a decade.)

These problems are happening in poorer communities, majority Black communities. But they’re also happening in wealthier communities too, wherever infrastructure is old. Chicago has lead issues in the water. The EPA office in Chicago [in September] found lead and Legionella in their water. This should be treated as a crisis. It should also be a priority to protect the Great Lakes. Politicians need to be rigid in terms of how much water can be pumped from the lakes and for what purposes. That’s not to say you can’t use water for industry, but that shouldn’t be the priority.

CH: What can citizens do to protect their own water supply or learn about potential threats?

JC: We need a lot more local involvement among community residents. I am not blaming residents in Flint or anywhere else, of course. But a lot of these backdoor deals — they’re happening at the local and state level right down the block from you. “More civic engagement” may sound corny, but you can’t [protect your water] if you don’t know what is happening at your local city council meetings. That’s where these things are happening.

I get it: It’s hard — people work and have to raise kids; they barely have any time. Right now, people are focused on the presidential election. In the years leading up to Flint’s crisis, there were activists trying to stop what happened in Flint. But think of the difference in impact between 50 activists and hundreds of local citizens.

CH: What can residents do to test their water or track issues?

JC: I wish I had a better answer. Unfortunately, residents have to become mini-experts. Do their own research, learn about water chemistry, contamination. The nationwide Environmental Working Group is a good resource. They have a thorough database where you can type in a zip code, and they tell you about water contamination. They are way more diligent than the EPA. I try not to be too cynical. Government agencies are not always trying to deceive. A lot of them just don’t have the expertise to tell you accurate information.

CH: What do you think are the biggest changes to the way we think of water issues since Flint received national attention?

JC: In my coverage of Flint and other communities, the biggest thing that has happened is that it has woken up normal Americans, who trusted their government, who were not overtly political people, who assumed government was there to help them, or fix things. In places with environmental health crises, people have become activists. Many more people are now taking action or staying more informed.

Jordan Chariton is the founder of Status Coup News, an investigative news network that aims to cover issues, such as environmental contamination, that the network feels are underreported in legacy media. Chariton’s book, We the Poisoned, can be found here in print, digital, or audio formats.

Photo by Katie Scarlett Brandt

Aaron Dorman is a reporter based in the Chicago area who specializes in environmental and/or technology issues. He doesn’t understand the difference between mostaccioli and baked ziti; thinks it might be a marketing scam.