With lead lurking in the paint, soil and water, many Chicagoans are at high risk

Like a civic superhero team, three city workers — a plumber, electrician and engineer — rang my doorbell one morning for our scheduled appointment. They had come to test our water after preliminary analysis showed high lead levels — 17 parts per billion (ppb) in our highest sample. Before getting started, they had one question: Had we used our water in the past six hours?

“Not since 11 o’clock last night,” I confirmed. One of the most nerve-racking parts of this process was making sure not to accidentally flush a toilet, rinse dishes or wash our hands. The water needed to be stagnant to get an accurate maximum reading.

The Chicago Department of Water Management engineer spent the next 45 minutes collecting samples from our kitchen. As he worked, the electrician and plumber inspected our water pump and the place where the electricity grounds to the water pipes.

My husband, meanwhile, stayed upstairs with our 9-month-old son: changing diapers, reading books, destroying block towers. The baby had spurred our first home purchase and inspired the lead test. We had hoped for the best when we sent it off, but we braced ourselves for the worst.

A world-class city at risk

When our son was 2 months old, we traded Logan Square for Portage Park. We thought it would be peaceful, but soon water main replacement — part of the city’s ongoing effort to replace aging water mains — blocked off one end of our street.

That same week, the Chicago Tribune ran an investigative piece that sowed fear in the general public: “Brain-damaging lead found in tap water in hundreds of homes tested across Chicago.”

Water mains — the large pipes running down the center of each street — aren’t made of lead, but the majority of service lines connecting water mains to individual properties are. That’s because Chicago required lead service lines until 1986. And when water main replacement projects quake streets, they can shake loose protective coating in pipes and disturb the lead, which then enters the drinking water.

Lead can also creep in by other means — through soldering in pipes, old valves and home fixtures. Installing new water meters can also cause lead disturbance.

Could the city be on the brink of a water crisis, like Flint, Michigan?

Chicago officials instruct residents with high lead water levels to install a filter that’s certified to remove lead and to flush their water system daily, which means running the water for three to five minutes.

Alderman Gilbert Villegas of the 36th Ward is alarmed. “We’re a world-class city, and we’re getting direction to use filters, to run your water for five minutes. This is not a second-class city or a third-class city. This is Chicago.”

Yet, while water has made a splash in the news, lead exists in other sources, too — especially in industrial cities like Chicago.

Because the federal government allowed lead in paint until 1978 and in gasoline until 1995, legacy lead still exists in paint chips in older housing; dust from decades of industry; and soil, where it settles from building demolitions and persists from past automobile exhaust. This puts all of Chicago’s 2.7 million residents at risk, from Lincoln Park to Garfield Park.

“Every zip code in Chicago is considered high risk for lead exposure,” says Poj Lysouvakon, MD, medical director of the Mother-Baby Unit at UChicago Medicine and a pediatrician at the Friend Family Health Center on Chicago’s South Side.

The dangers of lead

Lead, which is a heavy metal and neurotoxin, can permanently damage children’s developing brains and contribute to heart disease and kidney failure as people age. It poses the greatest risk to children age 6 and younger, when the brain forms new connections at rates unparalleled throughout life and prunes connections it doesn’t use. Exposure to lead inhibits this vital process.

The body excretes lead in small amounts through urine, but chronic exposure overrides that mechanism. Lead does more than damage developing brains. It can harm adults, too. A March 2018 study in The Lancet attributed 400,000 deaths a year in the U.S. to lead exposure, saying that low-level exposure to lead factors into deaths from cardiovascular disease.

However, the brain’s prefrontal cortex — associated with impulse control and decision-making — appears to take the hardest hit. Between 1979 and 1984, researchers repeatedly tested blood lead levels of babies born in poorer neighborhoods of Cincinnati. They then used imaging tests 20 years later and found that childhood lead exposure correlated with decreased gray matter volume in specific regions of the brain including the prefrontal cortex. Lead’s effect on brain development may be related to adverse cognitive and behavioral outcomes, they said.

Lead is particularly dangerous for babies and young children. But Helen Binns, MD, MPH, director of the Lead Evaluation Clinic at the Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, offers some reassurances.

Of the 1.1 million kids age 6 and younger who live in Illinois, only 3.5 percent have blood lead levels that surpass the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) reference level of 5 micrograms per deciliter, and 0.8 percent of kids have blood lead levels above 10. Overall, the average blood lead level in U.S. children of around 1.0 is low, Binns says, especially compared to the 1970s when it was 14.9 for ages 1 to 5.

Detecting lead

Government regulations vary in the amount of lead allowed in drinking water. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration prohibits lead above 5 ppb in bottled water, but the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) offers more wiggle room: 15 ppb.

Lead continues to be a concern. The Chicago Tribune’s analysis in April 2018 found lead in water drawn from 70 percent of the 2,797 homes that the city tested between 2016 and early 2018. It also said that three out of every 10 homes sampled showed lead concentrations above 5 ppb.

And in November 2018, news broke that City Hall neglected to publicly reveal that 17 percent of the homes they tested with newly installed water meters showed lead levels higher than the EPA’s action level of 15 ppb. Roughly 165,000 Chicago homes have these meters, which means as many as 28,000 could be affected.

Chicago resident Julie Lehto had requested a free lead test from the city after hearing that water meter installation might be raising lead levels. Lehto’s street, like mine, had undergone a water main replacement.

Worried for her 3-year-old daughter, she submitted water samples in June and received results in September. Her highest reading: 16 ppb.

With a level over the EPA action level, Lehto is now worried about the health effects of lead for her daughter. Twice Lehto asked her pediatrician to test her daughter’s blood for lead, and both results “were fine,” Lehto says. She might feel more at ease if she could watch her daughter for early symptoms of lead poisoning, but there typically aren’t any — until levels are exceedingly high.

“Lead poisoning is really insidious,” Lysouvakon says. “Signs can be as simple as abdominal pain, headache, high blood pressure or behavioral changes.” Physicians diagnose lead poisoning through a blood test, but lead can also reveal itself in imaging tests. Scans can show lead in paint chips in the stomach or intestines, and, in cases of long-term exposure, lead can be seen built up in the bones.

Lehto still worries about her daughter being exposed to lead in drinking water. “When she goes to the neighbors’ houses, I have to tell them about the water. I had to tell her daycare to use bottled water. I worry about friends’ birthday parties. It just angers me,” she says.

Invisible infrastructure

Lead service lines still exist in Chicago, and the city has no plans to replace them en masse. City officials have maintained that it’s a homeowner’s responsibility to get rid of lead service lines, because they’re on private property. Meanwhile, other cities like Madison, Wisconsin, have torn out lead piping and split the cost with homeowners.

Alderman Villegas says ward residents— in Montclare, Portage Park, Belmont Cragin and Hermosa — are surprised thatthe city hasn’t addressed the issue more drastically. Villegas encourages residentsto call 311 to request test kits immediately. “Talk to your state legislators about funding lead abatement programs and talk to your alderman,” he says.

First, I needed to talk to my son’s pediatrician. At his 6-month checkup, I shared my concerns. Doctors typically test children’s blood lead levels at their one-year appointment, but she reassured me that we could check now with a needle poke to his finger. Thankfully, his results came back normal.

Binns says that when she sees a child with high blood lead levels, she tries to ease parents’ concerns. She tells them, “We’re glad you found it early. Let’s really work on getting it down and keeping it down.”

She encourages parents to first look at their home. “Identify areas of peeling and chipping paint. Be aware of when your home was built,” as homes built before 1978 may have lead paint. “Be aware of demoli-tion and construction in your neighborhood,” she says. Lead-contaminated dust can land on indoor and outdoor surfaces, be tracked into the house where it gets on children’s hands or settle on toys and other objects that children may put in their mouth.

Lead in the schools

Lead in paint, soil and water is a big issue for schools in the Chicago area. Walls in old buildings with peeling lead- based paint need to be scraped and repainted. And the heavy metal makes its way into soil from industrial pollution, as is the case in large swaths of Chicago.

On Chicago’s far Southeast Side, George Washington High School chemistry teacher Melody Foley wants her students to know the risks, too. She and others in her department teach a lead unit, equipping students with plastic bags and gloves to collect soil samples. The classes partner with the University of Chicago for analysis.

Foley says her students hadn’t realized lead was an issue until a vast majority of their community samples tested positive. The class also analyzed the school’s water, comparing results with tests from Chicago Public Schools (CPS). “We wanted to get our own results to see what the procedure is to get good data,” Foley says.

Foley wasn’t shocked that lead was in the school drinking water. “I’ve been a teacher for 15 years, at this school for five. I’ve never drunk the water here. It’s brown,” she says.

Many of her students shrugged off the results. “They’ve become numb to the pollution. I would prefer outrage,” Foley says.

The school permits students to bring their own bottled water, which Lysouvakon also recommends. “Have your kids drink milk instead or bring a water bottle from home,” he says. “Be in touch with principals and ask if there’s a program or system for regularly flushing the water in the school’s pipes.”

CPS senior manager of construction Robert Christlieb intercepts lead concernsregularly. He manages 527 campuses with an average building age of 78.

Christlieb began testing CPS drinkingwater for lead in spring 2016, with a random selection of 32 schools. Of those schools, 25 had no traces of lead, six had levels below the EPA threshold of 15 ppb and one school had alarmingly high levels in three water fountains.

That set CPS on a mission to analyze all schools, focusing first on 294 elementary schools. Testing included 12,000 fixtures — mostly drinking fountains, but also kitchen sinks and other fixtures. “We did 60,000 lab tests within a six-month period. We slammed every lab in the state,” Christlieb says.

Results consistently showed that regardless of the school’s location or age, unused fixtures had a higher propensity for lead. “Our problem is what do we pick up in the building as the water sits? What is it brewing?” Christlieb says.

Finding best practices

CPS considered installing water filters, but opted against them, citing expenses and potential health issues if bacteria festered. Schools have manually flushed fixtures for one to two minutes after a day off school, but that’s been problematic, as building and weather issues often compete for the staff’s time. It’s time-intensive, too. At Lane Tech College Prep — the city’s largest high school — two employees took 4.5 hours to flush every plumbing riser in the school. A typical elementary school took 50 minutes.

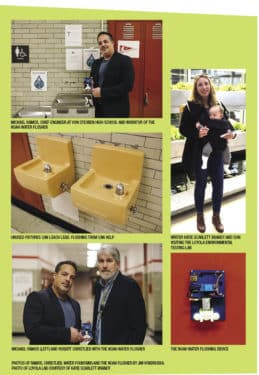

Then, Christlieb got a call from Michael Ramos, chief engineer at Von Steuben Metropolitan High School. Ramos had invented an auto-flushing device that affixes to drinking fountains, calling it “The Noah.”

The Noah, a computerized system that connects to a water valve, automatically opens and closes the valve to allow water to be flushed out, eliminating built-up particulates. Ramos also offers the system to residential homeowners through leadoutmfg.com.

Not only does The Noah keep lead from percolating, it also stimulates the application of orthophosphates — protective chemicals added to water to coat pipes and keep lead from leaching. Every time water runs, orthophosphates add another layer of protection to the pipes.

“We started realizing we were inoculating the building,” Christlieb says.

Each school can customize its flushing program based on how it uses water. With promising results, Christlieb is currently installing The Noah system at 25 elementary schools built in a range of eras — from pre-1900s to post-2000s. He’s budgeting $10,000 to $15,000 per school for the installation.

CPS has partnered with Zhenwei Zhu, PhD, an analytical chemist at Loyola University Chicago. Zhu runs the Loyola Environmental Testing Laboratory,a small commercial lab that offers local residents affordable testing for contaminants in soil and water.

Zhu is working with Christlieb to determine the best flushing protocol for each school to keep drinking water safe and waste less water. “We need to find the balance for minimum lead exposure and minimum drinking water wastage,” Zhu says.

The Loyola lab’s large ICP-MS machines can analyze soil and water for all inorganic contaminants in less than three minutes. After he runs a test, Zhu prepares a report with recommendations. For residents, the report suggests changes they can make in their homes and yards if results show lead.

“Best practice is, if you have high lead in your [soil], put down cover grass to minimize exposure from wind or kids playing. Also, don’t grow produce,” Zhu says. “If you’re doing urban agriculture, cover the soil and put down compost to separate it.”

I think about all of this while the water testing team packs up their samples at my house. My husband comes downstairs carrying our son as the engineer hands me a complimentary water filter. The men stand in a circle, smiling and cooing at the baby, who smiles back and claps his hands — a new trick.

He’ll be ready for breakfast soon, and as I prepare his food with water from the filter, I tell myself to stay calm, act on the things I can control and keep digging for answers.

Originally published in the Spring/Summer 2019 print issue

An award-winning journalist, Katie has written for Chicago Health since 2016 and currently serves as Editor-in-Chief.