Chicago’s Rich History of Cardiology Pioneers

Fact checked by Shannon Sparks

Chicago has a rich and fascinating history of heart-related firsts, from the first open-heart surgery to the invention of gel electrodes used in electrocardiograms. How did these groundbreaking developments come to reality, and where might they lead us next?

Whatever the future holds in terms of cardiology, there is no doubt that Chicago physicians and researchers will continue to play a vital role, unearthing and perfecting new therapies, and paving the way for the next generation of discoveries.

First Successful Open-Heart Surgery

It was a hot, Chicago summer night back in 1893.

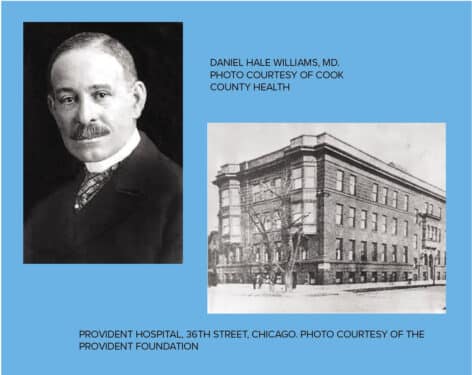

Daniel Hale Williams, MD, was at work at Provident Hospital when a young man came in with a stab wound to the chest.

James Cornish had been in a bar fight, and the knife had penetrated his heart. With no antibiotics and minimal anesthesia, Williams cut a small hole into Cornish’s chest. He used a salt solution to clean the wound, then repaired a severed artery and a tear in the pericardium, the sac surrounding the heart. Just 51 days later, Cornish walked out of the hospital, to live another 20 years.

Dr. Williams saw that a surgical repair was necessary, and no one had ever done that (successfully) before.”

“This was truly groundbreaking,” says Charles E. Bethea, director of curatorial affairs at the Chicago History Museum.

Bethea says at another hospital, Cornish likely would have lost his life, as African American patients weren’t accepted at “White” hospitals. “Due to racist practices, scores of individuals lost their lives from being transported from White hospitals to Black facilities,” he says.

Williams was a shoemaker and a barber before he became a doctor. He attended Chicago Medical College (now Northwestern University Medical School), graduating just 10 years before his landmark surgery at Provident Hospital. He himself had founded Provident just two years earlier because as a Black physician, he wasn’t able to practice surgery at other city hospitals.

“He was just one of three Black physicians (in Chicago) at the time he got his degree,” Fegan says. “And when he got his degree, this is less than 20 years after the Civil War.”

Provident Hospital, at the time of the surgery, had only 12 beds. “He was thoughtful and skilled,” Fegan says. “Because Black physicians could not get hospital privileges at that time, they were limited in terms of resources, of what they had access to, so this is pretty impressive.”

Word spread after Cornish left his hospital bed and continued on with his life.

“Ultimately, articles and papers were written about it,” Bethea says. “At the time, there were many attempts at surgery dealing with the heart. The patients did not survive. But under the tutelage, surgical care and expertise of Dr. Williams, Cornish survived.”

Eight decades after his historic surgery, musician Stevie Wonder honored Williams in the lyrics of his song, “Black Man,” singing: “Heart surgery was first done successfully by a Black man.”

Anko Chang, manager of operations at the International Museum of Surgical Science in Chicago, says, “All of the circumstances surrounding the surgery makes this a really amazing event in our medical history. Dr. Williams really gave people hope.”

Williams later left Chicago to become the head surgeon at Freedmen’s Hospital in Washington, D.C.

He eventually returned to Chicago, working at both Provident and St. Luke’s Hospital. He was the first African American physician appointed to the Illinois State Board of Health, and he was a charter member of the National Medical Association, which was founded because Black physicians couldn’t join the American Medical Association.

“He was just one of three Black physicians (in Chicago) at the time he got his degree. And when he got his degree, this is less than 20 years after the Civil War.”

Williams died in 1931, at age 73. “It’s a legacy he left in the United States,” Fegan says. “The lessons he learned paved the way for other advancements in medical care.”

But that legacy wasn’t limited to the heart. The Black people who trusted Williams with their medical care saw themselves reflected in him, instilling a level of trust and promise of what could be.

Identifying Risk for Heart and Vascular Disease

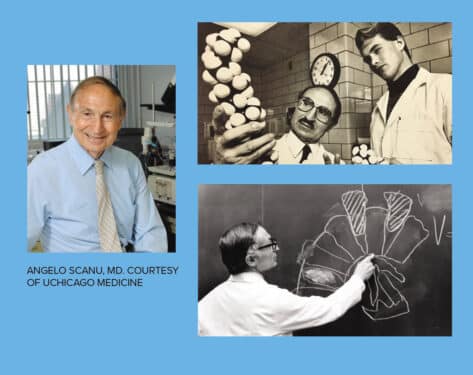

Angelo Scanu, MD, made a discovery in 1987 that “overnight made the field just go boom,” he said in 2009, as director of the University of Chicago Medicine’s Lipid Clinic. He had found that the structure of lipoprotein(a), a protein that carries cholesterol and triglycerides throughout the body, looks like plasminogen, an agent that dissolves blood clots. And because the two look alike, Scanu claimed, they competed. This prevented the body from effectively removing blood clots and increased the risk for blocked arteries and heart attacks.

“Lp(a) is a specific type of lipoprotein that is genetically inherited,” says Daniel Luger, MD, a preventive cardiologist at Rush University Medical Center. “It readily deposits into the artery walls and results in premature vascular disease.”

Scientists estimate that 1 in 6 people inherit higher levels of Lp(a) in their blood. Within that group, some are as much as three times more likely to develop coronary artery disease. And for people prone to blood clots, the risk is even greater.

Matthew Sorrentino, MD, interim chief of cardiology at UChicago Medicine, describes one potential treatment option that has grown out of Scanu’s findings. “Newer technology, based on how Lp(a) particles are formed in the liver, are under development and should be available soon [to] markedly lower Lp(a) levels.”

Sorrentino met Scanu in the late 1980s and worked with him initially as a cardiology fellow.

“Dr. Scanu was a very careful and meticulous investigator, always checking and rechecking his work to make sure it was accurate and reproducible. His studies showed that Lp(a) is an important risk factor for the development of coronary artery disease and heart attacks,” Sorrentino says.

Born in 1924 in Sassari, Italy, Scanu in 1955 was awarded a Fulbright scholarship to study biochemistry in the U.S. He made UChicago Medicine his professional home a few years later, in 1961.

Heart disease is the leading cause of death in the U.S. The American Heart Association reports that almost half of all adults in the country have some form of heart disease, and in many cases, they don’t know it. Coronary heart disease is the most common type, and it occurs when plaque builds up inside the arteries that supply blood to the heart. If enough plaque accumulates, blood flow to the heart is reduced or blocked, leading to a heart attack.

Doctors currently focus on decreasing risk factors besides Lp(a) that are more responsive to treatment. “If somebody has an elevated Lp(a), we aggressively lower their cholesterol with statins and PCSK9 inhibitors,” Luger says. “We also aggressively modify all other risk factors for cardiovascular disease. This means setting tight blood pressure controls [and] blood glucose targets, increasing physical activity, and improving nutrition.”

Scanu retired in 2011, and died in 2018 at the age of 93. Still, his legacy in Chicago lives on through the breakthroughs he pioneered. They continue to fuel cardiology innovations today. “He was a kind and caring doctor,” Sorrentino says. “I now care for many of his patients who remember him as a wonderful physician.”

Donald Rowley, MD, and the EKG

One of the most common tools in modern medicine — the gel electrode used to monitor heart rates in the electrocardiogram (EKG or ECG) — was born in Chicago more than 60 years ago.

“Let me tell you, it was a life-changing invention. There was no question about it,” says Elmer Murdock, MD, an interventional cardiologist at Midwest Cardiovascular Institute. “It’s been around for so many years, but it’s still the first line of treatment we have when diagnosing a heart issue. It’s also a really great screening tool and a very sensitive test.”

At the time, heart rate epidemiology intrigued Donald Rowley, MD — a pathologist and immunologist whose work greatly impacted basic knowledge of the immune system, organ transplantation, and heart disease.

Rowley spent half a dozen years toiling in his lab at the University of Chicago, trying to monitor a heart rate over 24 hours. First, he attempted it using a wristwatch because, he reasoned, heart rates were measured at the wrist’s radial artery. When that didn’t work, he enlisted engineers from Bell Laboratories to help him solder wires to dimes and secure electrolytic-coated dimes on their chests and forearms. Rowley and his colleagues converted a pocket watch into a pulse counter and connected the counter to the wired dimes, gluing the dimes to each test subject’s chest. Every time the subject moved, though, the electrical signal would scramble.

By chance one day, Rowley realized that a dab of gel on the dime cut the muscles’ electrical interference, and there he had it: an uninterrupted heart rate reading, even while the subject did push-ups or pounded on his chest.

The device birthed modern cardiology. “It allows us to determine the electrical forces that come out of the heart,” Murdock says.

In 1959, Rowley and his colleagues published an article in Science — essentially donating the work to the world instead of filing for patents.

To do so would’ve gone against academic culture, Rowley wrote in his memoir. And besides, he didn’t want to be a businessman; he was a scientist.

“He did it for the people, not out of financial gain,” Murdock says. “And this tech is still at the forefront of determining if someone has heart disease. It’s really the first test you reach for. When someone comes into the ER with chest pain, before you do anything, before they even check vitals, they do an EKG because it’s so instrumental to be able to see if the patient is having heart attack.”

Rowley died in 2013, at 90 years old, of congestive heart failure. He received little acknowledgment for the work his lab published on gel electrodes, and he was invited only twice to speak about the invention, despite its ubiquitous use worldwide. To him, however, the lack of attention meant more time to focus on other big questions of the heart and beyond.