Chicago groups find creative ways to provide fresh food and build healthy communities

On an unseasonably warm December morning, volunteers and staff from Advocate Aurora Health pull open cardboard boxes teeming with cauliflower, peppers, apples, greens, and string beans. The boxes are stacked in the Bethany Lutheran Evangelical Church parking lot in Chicago’s Calumet Heights neighborhood.

The workers carefully fill plastic bags with the fresh fruit and vegetables from the Greater Chicago Food Depository. Already a line of cars winds around the corner, as community members wait to pick up the produce and take it home.

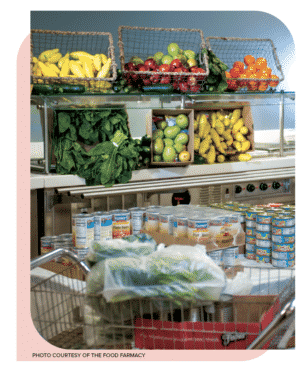

The drive-through food pantry is part of the Healthy Living Food Farmacy, a program that began in 2018 as a part of Advocate Aurora Health’s community services. Twice a month, as many as 85 people collect free fresh produce in an area with few other options.

Doctors from nearby Advocate Trinity Hospital, who treat people with nutrition-related illnesses such as hypertension and diabetes, can refer their patients to the Food Farmacy. For many, the fresh produce not only keeps them from hunger but also benefits their health.

Eating well is a critical component of maintaining good health and preventing and reversing disease. But eating healthily is easier said than done. Food deserts — areas that have few, if any, grocery stores — abound in Chicago, particularly on the city’s South Side and West Side, where access to affordable, nutritious food is often limited.

Healthcare centers, nonprofit groups, and urban farms are stepping in to close the food access gap. By creating programs that increase the availability of free or affordable healthy food, they are working to create healthy communities and prevent or reverse chronic disease.

Filling a need

The Food Farmacy exists to address those disparities, helping people overcome a barrier to healthy food, says Melinda Harville, team lead, Food Farmacy coordinator of community health for Advocate. “My first patient here, she’s one of the patients who always tells me, ‘You don’t know how the program has helped me. I’ve lost weight by eating the food.’ A couple other patients tell me, ‘I shop differently,’” Harville says.

When individuals pick up their food, hospital staff and volunteers offer suggestions on how people might cook that week’s produce. Replacing starches, like pasta and rice, with the healthy produce they’re taking home offers one way to manage health issues and prevent disease.

“If we focus on lifestyle, instead of managing disease with medicines, procedures, and surgery, we will then be able to reverse and heal from disease because we’re focusing on the root cause,” says Tony Hampton, MD, a family doctor at Advocate Aurora Health who helped launch the program. “That’s really what we need to change in healthcare.”’

To provide free or inexpensive healthy foods to underserved communities throughout Chicago, healthcare centers collaborate with food pantries to distribute fresh food, and clinicians demonstrate how to cook healthy alternatives. Urban farms sprout over entire city blocks, and farm stands bring locally grown produce to communities.

The city also focuses on improving food access through its Healthy Chicago 2025 initiative. The initiative aims to improve health equity and close the almost nine-year life expectancy gap between Black and white Chicagoans.

The plan supports efforts to make healthy food accessible via food pantries, food assistance, summer meals, and increased investment in local food producers and businesses. The whole city stands to benefit from the results.

Diet-related disease

Genetic makeup, sleep, stress, and the foods we eat all contribute to our health over time.

In general, Americans eat a lot of processed foods, which tend to be high in fats, added sugar, and sodium. Eating large quantities of such food over decades can wreak havoc on a person’s organs.

Poor nutrition is responsible “for many, if not the majority, of the medical problems that we treat,” says Katherine Tynus, MD, a primary care physician and center medical director at JenCare Senior Medical Center in Oak Lawn.

When people eat foods high in starches and sugars over time, it puts them at risk of developing insulin resistance, which can lead to type 2 diabetes. They may also develop metabolic syndrome, a group of conditions including elevated blood pressure, high blood sugar, unhealthy waist circumference, low HDL cholesterol, and high triglycerides. These conditions often lead to heart disease and stroke.

Having too much sugar and cholesterol floating around in the bloodstream can lead to inflamed blood vessels, causing blood clots that can result in a heart attack or stroke. Inflammation in blood vessels can also lead to damage in organs such as the kidneys and liver. It can cause fatty liver disease, obesity, and a range of cancers.

A 2019 review in the journal Metabolic Syndrome and Related Disorders found that only 12% of the country was in optimal metabolic health. “That means 88% aren’t,” Hampton says. “And all of these things lead to all these chronic illnesses.”

But by changing their diet and reducing their risk factors through lifestyle changes, individuals can prevent or reverse some of these conditions.

That’s why getting annual physicals and checkups is important. At the University of Chicago Medicine, Edwin McDonald, MD, a gastroenterologist and trained chef, who also runs The Doc’s Kitchen website, goes over a patient’s medical history, their eating habits, and lifestyle changes. He and his team offer tips on how to prepare foods that not everyone is used to eating, such as cauliflower rice, spaghetti squash, and quinoa.

Lack of access

Making lifestyle changes, however, can be difficult if neighborhoods don’t have places to buy healthy food at a reasonable price. In disadvantaged neighborhoods whose populations are primarily Black and Latinx, large swaths of areas don’t have grocery stores.

In the past few years, multiple stores that sell food on the South and West sides have closed, including Target in Chatham and Morgan Park, Save A Lot in Austin, and Aldi in West Garfield Park, leaving a gap in those communities.

A 2018 study published in the journal Health & Place showed that between 2007 and 2014 the number of grocery stores increased in Chicago, but food desert trends persisted.

“There definitely continue to be strong racial disparities in access to food,” says the study’s lead author Marynia Kolak, founding director for the Healthy Regions and Policies Lab at the University of Chicago.

Access to affordable fruits and vegetables is key. In many areas of the city, it’s easier and cheaper to find a burger or bag of potato chips than fresh fruit. Processed foods are usually inexpensive, easy to cook, and last a long time on store shelves. But they’re not as nutritious.

“For folks who are on a strict budget, buying fresh fruits and vegetables is often the last thing that happens because those items spoil quickly. If you have limited dollars, you often don’t buy fresh produce,” says Laurell Sims, co-founder of the Urban Growers Collective, a nonprofit that runs eight farms across the city and sells fresh food to people who would otherwise have little access.

Since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, the rate of food insecurity in the area has jumped 27%. According to Feeding America data, 9.3% of households in Cook County faced food insecurity in 2019, but that number was projected to rise to 11.8% in 2021. The rate is even higher in Black and Latinx households with children.

Creative approaches

Sinai Urban Health Institute developed an assessment a few years ago that helps community health workers identify patients struggling with food insecurity and diet-related illnesses by connecting them with partner organizations that provide more resources. One of those partners, the Sinai Community Institute, participates in the Veggie Rx program, where people get a prescription of sorts — for fresh fruit and vegetables.

The program targets people with diet-related diseases who are also experiencing food insecurity. In summer and early fall, participants receive a fresh produce box, plus they can take part in weekly nutrition education and cooking classes.

If we focus on lifestyle, instead of managing disease with medicines, procedures, and surgery, we will then be able to reverse and heal from disease because we’re focusing on the root cause.”

The Veggie Rx program — a collaborative effort from the Chicago Botanic Garden’s Windy City Harvest program, Lawndale Christian Health Center, and the University of Illinois Chicago’s Chicago Partnership for Health Promotion — allows residents get access to fresh, locally grown fruits and vegetables. That produce comes from unusual urban oases: city farms.

The Farm on Ogden in North Lawndale acts as a distribution center for the Veggie Rx program. Here, under vaulted glass ceilings, lettuce plants sprout delicate leaves. In another room, more greens thrive under purple grow lights. During the summer months, vegetables like chard, peppers, and tomatoes grow outside in neat rows that flank the greenhouse.

As part of Veggie Rx, people who get benefits from the federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) — available to people with a monthly gross income of less than $3,603 for a family of four — also receive double-value coupons that enable them to buy additional fresh produce at farm stands and receive twice the value that’s on their Illinois Link card with their SNAP benefits.

Community solutions

Various community-centered groups think creatively about how to bring fresh food to Chicago’s underserved communities, giving people alternative ways to get healthy foods.

One nonprofit, Gardeneers, teaches students from 19 schools in the city about farming by planting gardens nearby. The group has a farming curriculum, lets kids get their hands in the soil, and distributes fresh produce in the communities where it operates.

The Urban Growers Collective sells produce grown on its 14-acre South Chicago farm at farmers markets around the city. It also takes its fruits and veggies on the road.

Each week, its Fresh Moves Mobile Market, a food store on wheels, travels to 14 locations on the South and West sides, bringing affordably priced fruits and vegetables — including culturally important foods like collard greens and turnips — to health, community, and senior centers. In 2021, Urban Growers Collective provided $343,000 in free produce to customers through the Fresh Moves Mobile Market to help alleviate food insecurity.

“We want folks to eat things that they love,” co-founder Laurell Sims says. “So much of health is top down: This is good for you; this is bad for you. When we’re talking about fruits and vegetables, none of it is bad. Getting people to eat what they enjoy and then slowly introducing other options is really the best way to combat poor health outcomes.”

The benefits of better access to fresh produce might improve more than individual health, Sims says. “We know that when folks are healthier, they’re able to be better citizens and better neighbors because they have the food they need and the support they need to be able to participate in the community.”

Indeed, food can be medicine. And efforts from local community and healthcare groups are keeping it fresh.

Originally published in the Spring/Summer 2022 print issue

Susan Cosier is a Chicago-based writer focused on science and the environment. Her work has appeared in Scientific American and Science.