Groundbreaking CAR T-cell therapy engineers cells to target tumors

In fall 2013, when psychiatrist J. Barry Rubin, DO, developed hip pain, he attributed it to his new golf swing technique. Rubin, an active 72-year-old and avid golfer with a thriving psychiatry practice, was surprised when, after an MRI and biopsy, he was diagnosed with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and then with diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

Rubin went through standard chemotherapy and radiation treatment and, for a while, it seemed to work. Unfortunately, Rubin’s cancer returned, and in May 2016 he had a stem cell transplant. After six weeks of recovery, Rubin was back on the golf course. “I felt good, and I thought I was going to be okay,” he says.

Nevertheless, in August 2017, Rubin was again diagnosed with DLBCL, but this time it was stage 4. He started another chemotherapy regimen, but only to buy time.

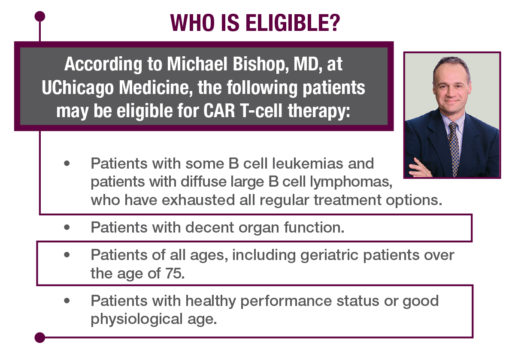

Rubin’s doctor told him about a trial for CAR T-cell therapy for DLBCL patients who had exhausted all their options. Rubin, who lives in the Detroit area, jumped at the chance and was placed on the waiting list at Detroit’s Karmanos Cancer Institute. But he was running out of time.

What is CAR T-cell therapy?

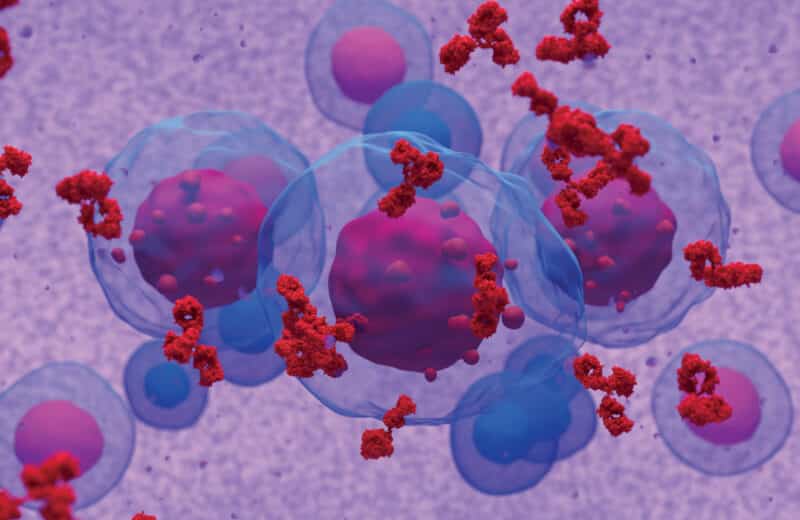

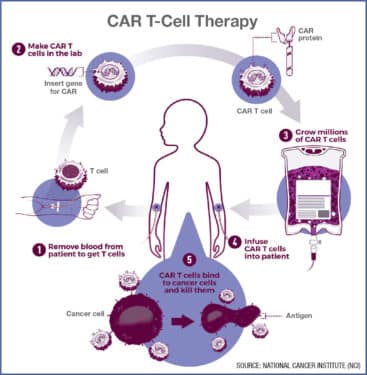

It all starts with T cells, which are a type of white blood cell that plays a key role in the immune system and fighting cancer. In CAR T-cell treatment, a patient’s T cells are harvested, sent to a lab and re-engineered by adding receptors called chimeric antigen receptors (CARs), which bind to cancer cells so that they can recognize, attack and kill them. The CAR T cells are grown in a lab until they number in the billions, then they’re returned and infused back into the patient. The engineered cells then seek out and kill specific cancerous cells.

“CAR T-cell therapy is a truly revolutionary therapy for patients with specific tumor types that appears to cure otherwise incurable cancer.”

In CAR T-cell clinical trials, 42 percent of patients with DLBCL were in complete remission after 15 months, according to Loyola University Medical Center, which participated in a clinical trial of CAR T-cell therapy published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

It’s a remarkable result, as the patients in the trial had previously failed all standard treatments. Some studies have also shown that CAR T-cell therapy is highly effective for patients with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, up to 90 percent of whom achieved remission in trials.

CAR T-cell therapy was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in October 2017 to treat patients with DLBCL. But it’s not cheap: The therapy costs $375,000 for a one-time treatment, and intensive care hospital fees can bring the total cost to about $1 million. Since the treatment is FDA approved, some costs may be covered by Medicare.

A tough treatment

Rubin, who did not have the luxury of time, set his sights on Chicago. UChicago Medicine was doing CAR T-cell therapy with amazing results, successfully treating patients over 65. Rubin called his niece, who is on staff at UChicago. She put him in touch with Michael Bishop, MD, professor of medicine and director of the Hematopoietic Cellular Therapy Program at UChicago Medicine.

In January 2018, Rubin had a CAR T-cell infusion at UChicago Medicine. So began the war within his body as the rapidly reproducing T cells sought and destroyed the cancerous cells.

The engineered cells are like missiles targeted specifically for a certain type of cancer — all while using the patient’s own T cells.

The side effects can be severe, though they’re rarely fatal, Bishop says. “These patients go through a short period that can be difficult, but they can derive such benefit,” he says. The benefit? Life.

Purer T cells

CAR T-cell therapy is starting to expand. In September 2018, Loyola University Chicago and Loyola Medicine received a $250,000 grant from the Leukemia Research Foundation toward the development of purer, less toxic CAR T cells to treat leukemia and lymphoma.

Loyola Medicine is working to purify the cells before they are put back into patients so they have fewer side effects, says Patrick Stiff, MD, Loyola’s director of hematology/oncology. Stiff is directing Loyola’s CAR T-cell research, along with Michael Nishimura, PhD, program director of immunologic therapies.

“When you take blood lymphocytes and put them in culture, you end up with a variety of cells, some of which are CARs, some of which are not. Some of these non-CAR cells could be producing some of the significant side effects we see,” Stiff explains. “We are going to purify these better so patients only receive CARs and hopefully less toxicity.” The purer CAR T cells will hopefully reduce long hospital stays and high costs, he adds.

CAR T-cell therapy is currently only commercially produced by drug companies. Loyola will be the first Chicago center to produce its own CAR T cells and will make them available to other centers in the Chicago area once initial testing is completed. The new CAR T cells should be approved and ready for the first trial by spring 2019, Stiff says.

Stiff says CAR T-cell therapy has the potential to be able to treat all kinds of cancers. “CAR T-cell therapy is a truly revolutionary therapy for patients with specific tumor types that appears to cure otherwise incurable cancer,” he says. A new strategy is being developed with universal CARs that could potentially be used with a variety of tumors, he says.

With its targeted therapy made from a patient’s own white bloodcells, CAR T-cell therapy has the potential to be a game-changer.

He’s grateful, he says, for “being alive and appreciative of it in ways I couldn’t imagine before. I’m not afraid of dying. If you are afraid of dying, then you aren’t living.”