How environmental contaminants affect heart health

From asthma to cancer risk, environmental contaminants affect human health in major ways. And research suggests that pollution also poses a significant threat to heart health specifically, increasing the risk of cardiovascular diseases.

Pollution (including noise pollution), chemical exposure, and the weather all affect the heart in different ways.

“The local climate can have an impact on cardiovascular symptoms — from the extreme cold temperatures of winter to the heat and humidity of the summer. This year has been especially unique with poor air quality making it unsafe for some outdoor activities for those at risk,” says Moeen Saleem, MD, cardiologist with the Midwest Cardiovascular Institute.

Air pollution — which stems mostly from automobile emissions, industrial processes, and fossil fuel burning — can cause inflammation and artery plaques. Heart attacks, strokes, and heart failure have been linked to prolonged exposure to air pollution.

Daniel Benatar, MD, is a cardiologist at Mount Sinai Hospital in Chicago. “When we’re talking about particulate matter, there are three types: large, fine, and ultrafine. The most worrisome of the matters is the ultrafine matter because it measures less than 2.5 microns, so it’s very, very small,” he says. “And the smaller the particle, the more it can get into your body — not only in your lungs, but into your bloodstream, cells, and, of course, your heart, which can be very detrimental.”

In 2023, the American Lung Association’s “State of the Air” gave Chicago an F-grade for number of high ozone days and high particle pollution.

Yet, air pollution doesn’t stop at the front door. It’s in your home as well. The Chicago Department of Public Health (CDPH) reports that 80% of homes in Chicago were built before 1978, when the federal government banned lead-based paint. Lead poses a serious risk to cardiovascular health, traveling in the form of dust particles, which people breathe in.

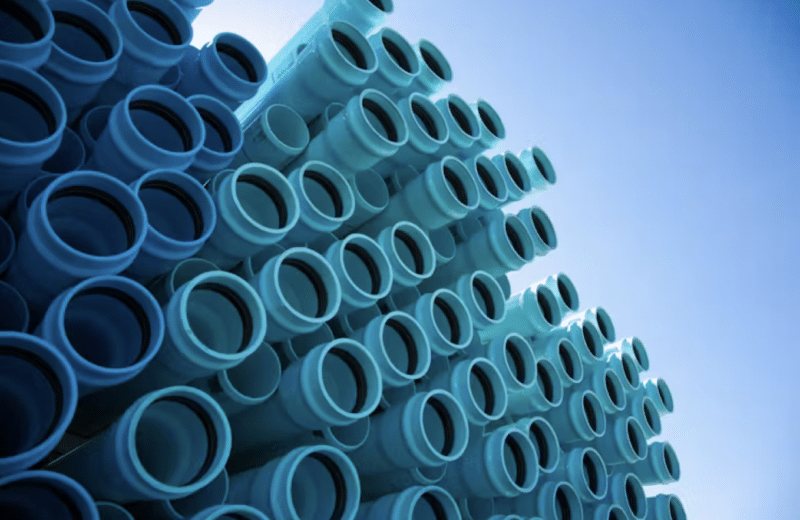

Heavy metals like lead accumulate in the body over time and disrupt normal heart function. Lead exposure has been linked to high blood pressure, heart disease, and stroke. Lead contamination in Chicago’s drinking water is a concern, too. While the city is beginning to take steps to address this issue in water service lines and aging infrastructure, it remains a significant threat to public health.

If you have other heart health risks, such as high cholesterol or obesity, and you add pollution and air contamination, “those risks become exponential. Therefore, the best way you may mitigate heart problems from contamination is decreasing the other risks,” Benatar says. “Diet, exercise, and quitting smoking are things we can control.”

To reduce exposure to air pollution, Benatar repeats a familiar line used during the pandemic: wear a mask. “If you think the air is going to be very contaminated, wearing a mask helps decrease the particulate matter and other contaminants,” he says.

Chicago is home to numerous industrial facilities, some of which release pollutants into the air and water. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) identified several areas in the city as having elevated levels of toxic air pollutants, primarily areas near expressways and industry.

Similarly, exposure to pesticides and industrial chemicals have been associated with an increased risk of heart rhythm abnormalities, atherosclerosis, and heart failure.

And one of the most overlooked pollutants of all, noise pollution, is another environmental contaminant that affects heart health. Like all densely populated cities, Chicago faces challenges related to noise.

Chronic exposure to excessive noise — traffic noise, construction activities, and loud workplaces — can lead to stress, sleep disturbances, and increased blood pressure. Prolonged exposure to noise pollution has been associated with an increased risk of heart disease, including hypertension, heart attacks, and stroke.

“Poor air quality and pollution can be stressful for those at risk for cardiovascular disease,” Saleem says. “That’s why it’s important to have a cardiac risk assessment and targeted treatment.”