While people with Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia gradually lose the ability to speak and to remember, the arts can help ground them, keep them engaged and let them express themselves.

“The arts enrich the quality of life of individuals with memory loss and provide them with a sense of purpose and meaning,” says Darby Morhardt, PhD, LCSW, associate professor in the Mesulam Center for Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer’s Disease at Northwestern University. “The arts are a mode of expression when cognitive abilities are declining.”

Art helped North Shore resident George Taylor connect with his 73-year-old brother, Charles Taylor, who has frontotemporal dementia, which can affect the ability to use language. A former artist, Charles had exhibited his paintings in art shows throughout the Chicago area.

George, who asked that his and his brother’s names be changed for privacy, says that participating in an event at the Art Institute of Chicago gave his brother a chance to express himself.

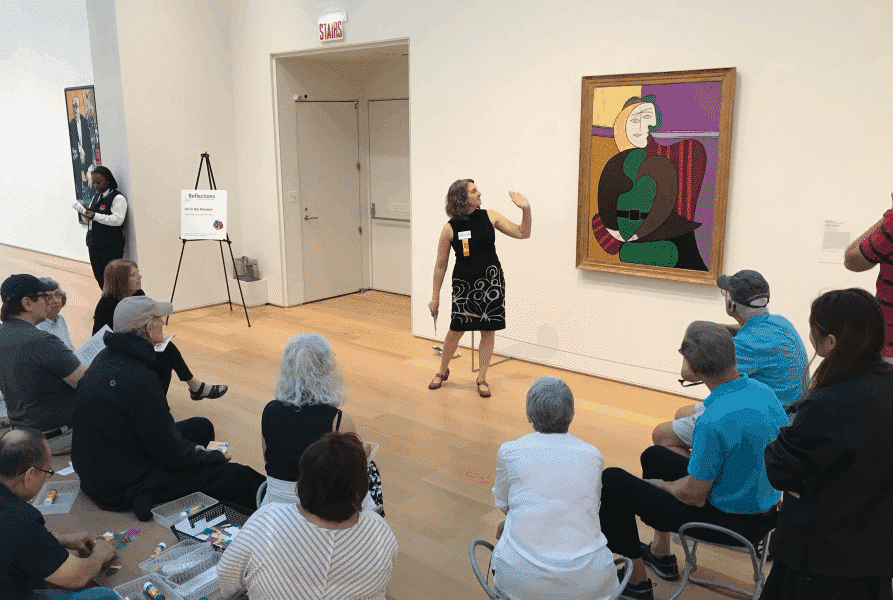

The Art in the Moment program, held at the Art Institute in partnership with the Mesulam Center, is designed for people with memory loss to attend with a family member. During a recent program, docents invited participants to explore portraits, including one by Pablo Picasso.

As they talked about the art, Charles was able to express his emotions, George says. “The docents asked us for our own ideas about what we saw in the paintings — the mood or the personality of the person or why certain colors were chosen — and Charles gave a couple of his opinions,” George recalls. Participants also decorated coasters with pieces cut from a reproduction of a Picasso painting.

Morhardt says Art in the Moment provides intellectual stimulation and an alternative means of communication in a safe environment. Its creators based it on a program developed by the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

“The art project isn’t reliant on memory,” Morhardt says. “It involves using the imagination to express themselves in the way they are able.”

Music matters

In addition to visual art, music acts as a grounding force for people with dementia, too.

In Alzheimer’s disease, the area of the brain where memories of music are processed remains intact, says Borna Bonakdarpour, MD, a behavioral neurologist at Northwestern Medicine.

“People with dementia feel confused and lost in space and time. Music takes them back to a place and time where they felt safe and they felt good,” Bonakdarpour says.

Because the areas that process music in the brain also overlap with those of emotion, listening to music can decrease symptoms of depression and anxiety, Bonakdapour says. He’s witnessed people with dementia become livelier and more conversant when they participate in musical activities. Their social engagement with care partners improves, too, he says.

Other creative art forms can also improve the quality of life of people with memory loss. Dance and movement therapist Erica Hornthal, who belongs to the Arts for Brain Health Coalition, a collaboration between healthcare providers and arts groups, sees communication as more than what people express verbally. “Movement is a very inherent, primitive way to express emotions, tap into memories and unlock cognitive potential,” she says.

Regardless of the specific art form, Hornthal adds that through music and the arts, “A lot of family members and friends who thought they had lost their loved one see them come alive again.” George and Charles Taylor agree.