By Patrick Kenney

No elective surgery has attained as widespread an appeal and acceptance as has LASIK. Over the last couple decades, particularly since the Federal Drug Administration’s (FDA) approval in 1999, the procedure of laser in-situ keratomileusis has corrected the vision of millions of people, giving the rather extraordinary process a mundane quality—like a haircut. Something to do while you wait for the dry cleaning.

As the profitability of the enterprise grew, so did the number of LASIK centers around the country, and the awareness of LASIK expanded. Today, it is so thoroughly advertised and available, that many people who don’t even need glasses or contacts will seek out this surgery under the assumption that it will make their eyes stronger. But this is something LASIK cannot do.

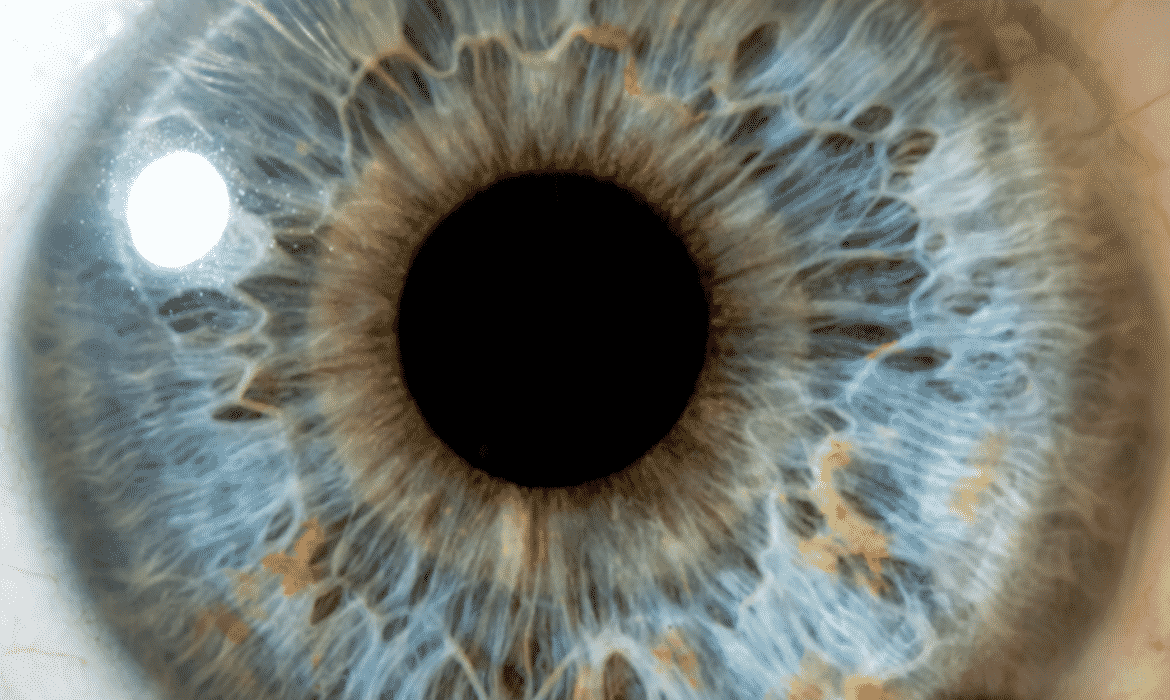

It is, however, the most modern and most common approach to refractive eye surgery. The procedure involves using a laser to cut a small flap away from the surface of the eye and reshape the cornea beneath, whereupon the flap is replaced. Earlier forms of LASIK surgery used a microkeratome blade to create the flap, but today, the laser-only approach has become the norm.

While the procedure is enormously successful, with nearly immediate recovery and low rates of complication, it’s still not a miracle cure for compromised vision.

“We need to make sure that the expectations are realistic, and we explore that with the patient,” says Dr. Robert S. Feder, explaining what he thinks is one of the most important parts of the consultation process. Feder is an associate professor of ophthalmology at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine, and one of several surgeons there stressing the importance of building a rapport with the patient from day one.

Phil Winkelman, a 32-year-old Chicagoan and an account director at a market research firm, underwent LASIK surgery in his twenties. “The whole procedure is a little scary,” Winkelman says. “You get cuts on your hands or your arm… you know what that feels like, but when they just slice part of your eyeball, it’s like ‘Oh that’s an interesting feeling. I’ve never felt that before.’”

Winkelman chose his surgeon, Dr. Colman Kraff, of Chicago’s Kraff Eye Institute, based on his reputation as one of the nation’s leading doctors. Winkelman was determined that if he was going to commit to going through with LASIK, he was going to go to the best surgeon he could find.

“[Dr. Kraff] was the very first surgeon doing this procedure in this area and one of the first in the country,” writes Sarah Stradone, a refractive counselor at Kraff Eye Institute, in an email to Chicago Health. “He wants to be part of [his patients’] whole experience, meeting them at the consult, preoperative exam, surgery and all postop appointments in the first year.

Winkelman was pleased to hear that he would be a good candidate for the surgery. “I’ve had glasses since I was 7 years old. I had really bad eyesight, like a -7.5 in one eye and -6.75 in the other,” meaning that without his glasses, even if you were sitting right next to him, “I wouldn’t know who you were,” Winkelman says.

Though he was aware of the surgery’s projected outcome, Winkelman was surprised by the immediate clarity of his vision the moment after the laser surgery was completed and the flap was replaced. “It was crazy. Absolutely crazy,” he says.

But postsurgery, Winkelman did experience haloing around lights at night, which the team at the Institute had warned him would be a likely side effect. “They [Kraff Eye Institute] made sure that I knew [that even if] it wasn’t going to be absolutely perfect—it was going to be a lot better,” he says.

LASIK isn’t limited to prestigious organizations like Kraff Eye Institute or leading research hospitals like Northwestern. A proliferation of storefront LASIK centers offer the surgery at bargain prices, often around 20 percent less than organizations like the aforementioned.

One such LASIK center is LasikPlus in Lincoln Park and dozens of other locations across the country. LasikPlus isn’t shy about the sale. “Save $600 or more on LASIK” is the first message it drives home. And when visiting the corporate website, you discover that LCA Vision (the parent company of LasikPlus) highly prioritizes investor relations.

Dr. Mirjana McCarthy, who works at the Lincoln Park location, emphasizes that LasikPlus uses equipment of the highest caliber, comparable to Kraff Eye Institue. And with more than one million surgeries performed nationwide since 1995, LasikPlus is hardly the bargain basement in terms of quality of outcome.

So how does a storefront like LasikPlus effectively provide the same surgery that a leading research hospital like Northwestern performs and do it at a lower cost to the patient? Well, one big way is the reduced amount of time each patient spends with the surgeon.

McCarthy is an optometrist, the same type of specialist who examines your eyes and prescribes your contacts and glasses. But only an ophthalmologist, an eye surgeon with a medical degree, who can also treat all diseases of the eye, can actually perform LASIK surgery. At the Lincoln Park office of LasikPlus, the surgeon, Dr. David King Aymond, works with McCarthy, performing LASIK surgeries, based on her recommendations and data gathered by a technician.

This means that patients at LasikPlus might only see the surgeon on the day of the procedure, and barring the need for a second surgery, that’s likely the last time they’d see the surgeon.

The teams at Kraff and Northwestern recommended considerations beyond the price point. Sarah Stradone, the refractive counselor at Kraff, writes that “[patients] should always consider the experience of the surgeon, not just how many surgeries [the surgeon has] performed, but how much experience in postoperative care the [surgeon has had].”

“We stand out because we have a doctor-to-patient quality metric that I think is pretty much unparalleled,” says Dr. Nicholas J. Volpe, professor and chair of the Department of Ophthalmology at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine. “Surgeon-driven, in control from start to finish. There’s no third party who’s sending you to a LASIK center for surgery with someone you’ve never met before.”

But McCarthy insists that Aymond isn’t just the man behind the curtain. “We always give patients the option to schedule a time to meet with [Dr. Aymond] before their surgery; they don’t have to meet him [for the first time] on the day of surgery.”

However, meeting Aymond on the day of surgery is standard procedure and is what most patients end up doing. “Even on days when he’s here, and it’s not the day of the patient’s surgery, I’ll let the patient know that ‘Dr. Aymond is here today doing surgery; let me know if you’d like to meet with him.’ A lot of times [they say] ‘No, that’s okay, you’ve answered all my questions, and I’ll just meet him on the day of,’” says McCarthy.

“Some patients voice concern that he’s not doing their consultation. But by far, the majority of patients whom we see usually meet with [Aymond] on the day of [surgery].”

At Northwestern Ophthalmology (where Feder is a surgeon), the surgeon does your consultation, performs the surgery and provides whatever postop care may be needed. That sort of special attention comes at an extra cost, but for a lot of patients, it provides extra peace of mind as well.

“Many patients have said to me over the years, ‘I really appreciate the time you took to speak with me,’” Feder says. “There is information that you sometimes don’t take away from a video tape.”

At Northwestern, you’re getting “the highest level of quality and compassionate care with physicians who are the teachers and trainers of other LASIK surgeons,” says Volpe.

But across the country, millions of people are willing to forgo the sort of specialty care that Volpe and Feder pride their hospital on.

“Most patients don’t want to do a bargain eye surgery,” McCarthy says. “They want to get the technology that is best for them and the newest technology on the market, but they also don’t want to pay an arm and a leg for it.”

Originally published in Chicago Health Summer/Fall 2013