Antibiotic-resistant bacteria are spreading steadily

Antibiotics have dramatically changed human health, effectively treating once-menacing infections. Unfortunately, in many instances, we have been overexposed to these drugs, weakening their impact and creating an epidemic of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

“The development of antibiotics was one of the greatest advances in human medicine,” says Sameer Patel, MD, MPH, an infectious disease specialist at Lurie Children’s Hospital. “But if you give a medicine to kill an organism, eventually there will be a few [bacteria] that figure out a way to adapt.”

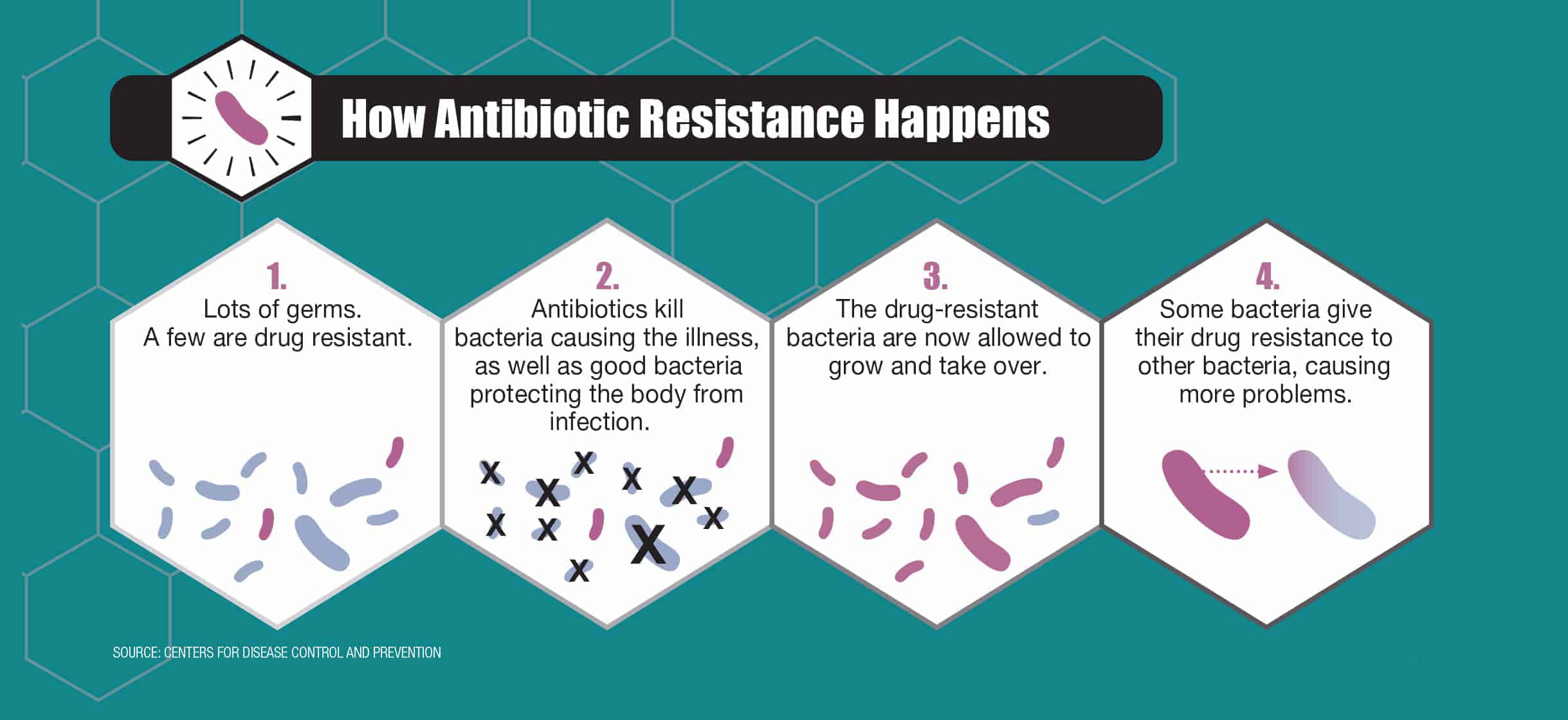

Over time, the resistant bacteria—the mutants—become the predominant organism, no longer responding to typical antibiotic regimens. Antibiotic-resistant bacteria can spread, unchecked, through hospitals, communities, cultures and continents.

The worst of these resistant bacteria are dubbed superbugs, says Mary Hayden, MD, infectious diseases physician and director of the Division of Clinical Microbiology at Rush University Medical Center. A superbug has two distinctions: one; it’s so multidrug resistant that it leaves very few options for treatment, and two; it spreads rapidly across large geographic regions. She says that the rate of these superbugs—and in fact all antibiotic-resistant bacteria—is increasing steadily.

Widespread antibiotic resistance is due to profligate antibiotic use, environmental contamination and nature itself, notes Robert A. Weinstein, MD, professor of medicine at Rush University Medical Center. Even the healthiest among us are exposed to antibiotic-resistant organisms—from our soil, our food supply, the air and each other.

“Doctors are prescribing too many antibiotics too frequently for infections that later turn out to be viral and, therefore, unresponsive to antibiotic treatments,” Weinstein says.

For instance, when a young child has an ear infection, physicians used to routinely prescribe antibiotics. But most children get better on their own within two or three days without intervention. Taking antibiotics when they’re not needed can make it hard for the drugs to work in the future.

Antibiotics are also given to livestock and poultry to promote growth. While agricultural regulations ensure that there is little risk of the antibiotics making their way into your body (and the antibiotics are digested by the animals before slaughter), resistant organisms in animals can make their way through the food chain.

The data is daunting. About 700,000 people worldwide die annually from antibiotic-resistant infections, with 23,000 of those deaths occurring in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A report from the Review on Antimicrobial Resistance estimates that if we continue on this path, the global number will rise to 10 million antibiotic-resistance–related deaths per year by 2050.

Hospitals have made strides in their efforts to restrict the spread of resistance. Cook County and Rush hospitals make up the Chicago Antimicrobial Resistance Prevention and Intervention Epicenter (C-PIE), one of 11 national CDC-funded programs aimed at collaborative research and control of antibiotic resistance.

“One of C-PIE’s most successful developments has been the use of chlorhexidine bathing—a method of cleansing ICU patients that removes resistant bacteria from their skin, thus helping stem the spread of resistant organisms to other susceptible patients,” says Weinstein, who serves as C-PIE’s principal investigator.

The Epicenter has also introduced a tracking tool—the XDRO Registry—to trace the spread of a widespread class of superbugs often detected in acute and long-term healthcare facilities. Hospital groups work together for a coordinated regional approach to examine trends and direct their focus to particularly problematic areas.

To curb the crisis, Patel says that major changes need to occur, including more judicious antibiotic use and monitoring, faster development of new drugs and limited use of antibiotics in food production.

The biggest inhibitor? Humans. Changing protocol is easier said than done, and there is often pressure on doctors to prescribe antibiotics first and figure out what’s wrong later.

“We do need antibiotics to combat infections,” Patel says, “but by using them wisely, we can prevent the increase in the rate of resistance and, therefore, have our antibiotics work when we need them.”

In March 2015, the White House released a national plan to combat antibiotic resistance, which includes mandated antimicrobial stewardship programs in hospitals under CDC guidelines, reduced antibiotic use in outpatient and acute care facilities, improved national monitoring systems and the elimination of medically important antibiotics from the group of drugs used for growth promotion in animals.

These changes are necessary—our lives depend on them. What does our future look like if things don’t change? Put simply by Weinstein: “We don’t want to find out.”