Major innovations in cardiac treatment happening right here in Chicago

There are some fields of medicine where advancement is happening at such an astounding pace that it’s unfathomable to think how different treatments were 10 years ago — and how different they’ll be 10 years from now. In the world of cardiology, progress in treatment has boomed in the past decade, especially in Chicago, home to some of the nation’s top hospitals for cardiac care.

“Innovation is key,” says Allen Anderson, MD, cardiologist with Northwestern Medical Group and medical director of the Center for Heart Failure at Northwestern’s Bluhm Cardiovascular Institute. “One of the things I tell my patients is, ‘I don’t have to keep you going forever, just until the next best thing comes along.’”

Fortunately for heart patients, the next best thing is often making its way through clinical trials at that very moment. Cardiovascular disease — including coronary artery disease, heart failure, stroke and high blood pressure — is a principal killer of Americans, accounting for about one in four deaths, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). But tremendous strides have been made in the development of medical therapies.

Look back 25 or 30 years and there wasn’t much a physician could offer a heart patient aside from transplantation, which didn’t always work very well. Today, innovations indicate a future where failing hearts can be treated — and even restored — like never before.

Replacing valves

At Northwestern Memorial Hospital (NMH), researchers and physicians are developing new strategies to fix structural abnormalities of the heart and prevent heart failure from occurring.

“We have techniques for all of the valves of the heart that are in various stages of study,” Anderson says. Instead of repairing or replacing heart valves through open heart surgery, less-invasive techniques are available.

Charles Davidson, MD, clinical chief of cardiology at NMH, has spearheaded the use of transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR), a less-invasive option for high-risk patients with blocked aortic valves. Recent advancements make it an increasingly better option for patients who want to forego open heart surgery, previously their only option, he says.

Blocked heart valves restrict blood flow and put undue stress on the heart as it attempts to pump blood past the narrowed opening, so it’s important that treatment occurs early. “Blocked aortic valves are associated with an almost 50 percent mortality rate in the first two years after symptoms develop,” Davidson says.

The TAVR approach involves placing a catheter into a patient’s femoral artery. The catheter is expanded with a balloon and replaces the functioning aortic valve. New iterations of the catheter are smaller, more flexible and easier to insert than previous ones, Davidson says, allowing NMH to use them in more patients.

Patients are generally home and able to resume normal activities within three days, as opposed to the weeks to months typically required to recover from open chest surgery. NMH is currently participating in a clinical trial testing TAVR with low-risk patients, potentially offering an early solution for younger, healthier patients.

Restoring circulation

Heart failure, which the American Heart Association cites as being responsible for 8.5 percent of all cardiovascular disease deaths, is the inability of the heart to efficiently pump blood. Preventing heart failure is an important part of what cardiologists do, but the disease continues to affect 5.7 million Americans a year, according to the CDC.

Continuous-flow heart pumps have been the go-to treatment to help failing hearts push blood through the body, but the pumps require open chest surgery and can come with a myriad of major complications, says Valluvan Jeevanandam, MD, chief of cardiac and thoracic surgery at University of Chicago Medicine. Because of that, Jeevanandam says, many patients wait until they are very sick before getting the pumps.

Cardiovascular disease as a cause of death in America is decreasing because we’re attacking successfully on all fronts”

Jeevanandam is currently involved in a clinical trial investigating NuPulse, a minimally invasive alternative to traditional heart pumps. The ambulatory, long-term device — referred to in the medical community as an intravascular ventricular assist system, or iVAS — has even shown the ability to restore efficient heart function.

NuPulse, which requires just a small incision below the clavicle, functions as a counterpulsation device, creating much-needed energy in the circulation and helping the heart function until a transplant or other type of advanced treatment is necessary or available.

Thirteen patients listed for transplantation received NuPulse in its first human trial at University of Chicago Medicine, which began in 2016. Three of them — who Jeevanandam calls “super-responders” — were eventually able to spend upwards of 12 hours off the device at a time.

While the pump is currently being tested on patients awaiting a heart transplant, the ultimate goal is to have patients be able to take the pump home as permanent therapy.

“It’s a ‘why not?’ device,” Jeevanandam says. “Why wouldn’t you put this in and see how the patient does? If it’s not enough support for them, you can advance support. If

it is, then maybe you’ve bought them many years before they need advanced support, or maybe they recover enough that we can wean them off the pump entirely.”

Next up for NuPulse is a trial expansion, which will test the device in patients who are not in dire need of transplantation and will try to determine the factors that make a patient a super-responder.

Advanced support

Fortunately, patients who require advanced support — such as a valve repair, removal of a cardiac tumor or coronary artery bypass — also are benefiting from major innovations in minimally invasive surgical techniques.

At the University of Chicago Medicine, specialists perform many different varieties of heart surgery — including valve surgery and heart rhythm correction procedures — using da Vinci robotic technology.

Husam Balkhy, MD, director of minimally invasive and robotic cardiac surgery at University of Chicago Medicine, is a leading physician of the robotic approach for cardiac surgery. In traditional open chest surgery, surgeons saw the sternum in half to access the heart. In da Vinci robotic cardiac surgery, the surgeon uses a computer console to precisely control surgical instruments on the robot’s four arms.

Instead of opening the chest, surgeons perform delicate incisions on the side of the chest between the ribs. Cameras inserted in the incisions provide visibility without the need to open the sternum, reducing pain, disability and recovery time.

Robotic surgery utilizes the latest technological advances while minimizing trauma compared to traditional approaches. “I do heart surgery every day, but only about 10 [traditional] open chest surgeries a year,” Balkhy says. The da Vinci robot is constantly improving, offering additional functionalities that allow for more precise, more advanced minimally invasive surgeries.

One exciting recent advance, Balkhy says, is a mini-stapler for coronary artery bypasses. The staples allow surgeons to “automate, standardize and make reproducible the act of connecting bypass grafts to the small heart arteries,” he says, creating a new pathway for blood to pump with a significantly less-invasive approach than what would traditionally be used.

Significant advancement is happening in transplantation, too. Anderson points to new perfusion technology that can keep a heart beating on its way to a transplantation procedure. The development — colloquially called “heart in a box” — allows a heart to beat and circulate blood outside of the body until it is ready for transplant surgery. In a transplant situation, where every minute counts, the heart can be viable for longer, enabling better transplant access to patients in remote areas.

Anderson says he’s hopeful of a future where heart disease is a more manageable illness. “Cardiovascular disease as a cause of death in America is decreasing because we’re attacking successfully on all fronts,” he says. “While mortality is inevitable, we can improve quality and quantity of life by better managing cardiovascular disease — ultimately giving our patients a chance to grow old.”

Considering the rapid rate of advancement, many more patients will be able to treat heart failure successfully with the help of these new technologies — and that is heartening news indeed.

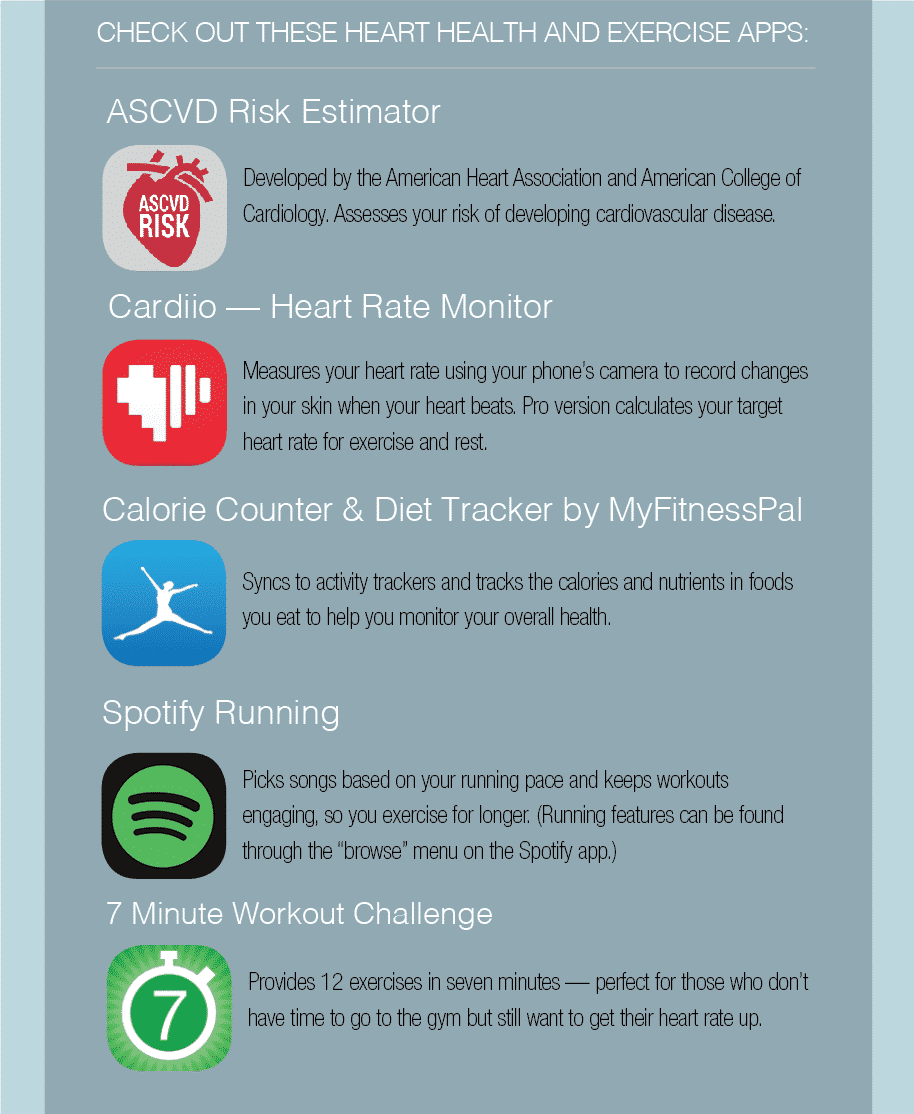

Using Apps for Heart Health

“There’s an app for that” the saying goes, and that’s certainly true for cardiovascular health. Whether you want to check your heart rate, track your blood pressure or get tips on keeping your heart strong and healthy, you can find an app that matches your interest and needs. Just be aware that fitness and heart health apps may not always be accurate, cautions Martha Gulati, MD, editor-in-chief of the American College of Cardiology’s CardioSmart website.

If you’re interested in an app that will take a measurement like blood pressure, make sure it’s been approved by the Food and Drug Administration, Gulati advises. You can find examples of approved apps on the medical device section of the FDA website. Apps that are not medical devices do not need FDA approval.

An app is never a substitute for advice from your healthcare provider. “Formulas in your devices that give certain information may or may not be accurate,” Gulati says. “Your Fitbit, phone or other technology may not accurately measure steps.”

Technology can get you moving and provide you with valuable fitness feedback. So start tracking your health with the latest apps. — Julie A. Jacob