There’s no cure, but researchers are hoping to prevent the most common type of dementia

Traffic unexpectedly slowed on Green Bay Road through Winnetka. Glenview resident Jean Buchband was running errands following a workout session across town. After what felt like an eternity of riding her brakes and getting nowhere, the problem car pulled onto the shoulder. Buchband couldn’t help rubbernecking as she passed the culprit—a confused and lost older woman. It was her mother.

Her mother was supposed to be at the Northbrook Public Library. She had no business being in Winnetka. “What are you doing here?” her mother asked, after Buchband pulled off the road. Right away, Buchband knew that this confusion was more than just being lost.

“Let me lead you home,” she told her mother.

Losing the long game

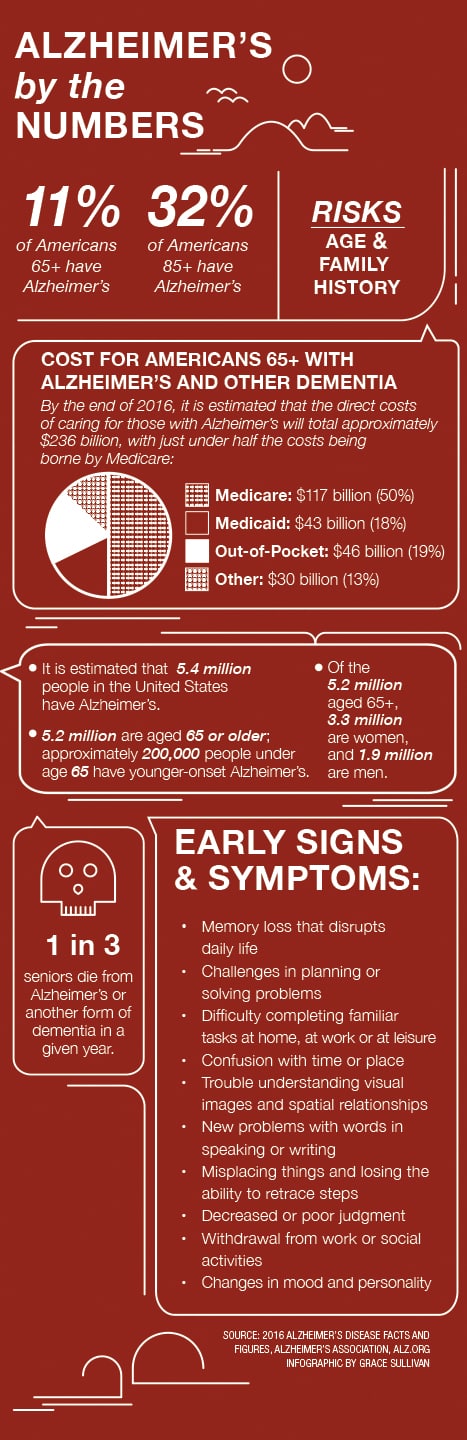

Buchband’s mother has mild cognitive impairment, a precursor to dementia. As her dementia continues to progress, she will join the estimated 5.4 million Americans living with Alzheimer’s disease.

Alzheimer’s, a degenerative brain disease, occurs when neurons stop doing their job—that of sending communications from one part of the brain to the other. As two different kinds of abnormalities —tangles and plaques—accumulate in and around neurons, the nerve cells die, our memory progressively fades, our personality becomes unfamiliar to those around us, and we lose control of our thought processes and ultimately our motor skills.

As the disease moves along its continuum, loved ones can do little more than watch the descent into helplessness, loneliness and, finally, death.

Once dementia strikes, there’s no turning back, and there’s no successful treatment. “There’s not much we can do in the way of interventions if a person is starting to have Alzheimer’s,” says Maria T. Caserta, MD, PhD, vice chair of clinical services, medical director of Inpatient Psychiatry and co-director of the Memory and Aging Clinic in the Department of Psychiatry at University of Illinois Hospital & Health Sciences System. “Some people can stay in the mild cognitive impairment stage for a long time. We don’t have a good way of knowing with which patients we should start medications.” The medications, Caserta says, have a modest effect on slowing the cognitive decline that ends in Alzheimer’s.

Buchband’s mother was as sharp as they come. A chemistry teacher in her native Taiwan, she immigrated to the States, learned English, went to night school and became a successful computer programmer.

“She was always my role model of how a person should be,” Buchband says. But she’s seen a steady decline. Shortly before her father passed away from cancer in 2006, he warned her that Alzheimer’s runs in her mother’s family. “After Dad passed, and Mom moved to Chicago, I saw little clues that something was the matter. She’s still able, but I don’t know how much longer that will be.”

Switching things up

“We have to do something different because what we’re doing today is a failed approach,” says Demetrius Maraganore, MD, medical director of the NorthShore Neurological Institute and chairman of the Department of Neurology at NorthShore University HealthSystem.

Watching Alzheimer’s symptoms arrive and begin wreaking havoc is obviously not ideal. The focus, he says, should be on early prevention.

There are an estimated 220,000 people in Illinois living with Alzheimer’s, according to the Greater Illinois Chapter of the Alzheimer’s Association, but an estimated 1.5 million Illinois residents will get it in their lifetime. It’s not that we should stop treating the 220,000 afflicted, says Maraganore; it’s that we should not ignore the 1.5 million at risk.

NorthShore’s Center for Brain Health aims to prevent Alzheimer’s with its Alzheimer’s Prediction Model developed by doctors at the center. The center is part of NorthShore’s Center for Personalized Medicine—one of the few facilities with the latest advances to treat, and in some cases prevent, the illness based on a patient’s genetic information.

The Alzheimer’s Prediction Model looks through the electronic medical records (EMRs) of tens of thousands of NorthShore patients for historical risk factors and outcomes. Using that information, Maraganore says the model can predict with 95 percent accuracy which people over the age of 60 will develop Alzheimer’s within five years. The information is already being incorporated into the standard EMR so that primary care physicians can be aware of the risk and treat the patient earlier, before the disease advances.

At this point, medications are not very successful at slowing or stopping the progression of Alzheimer’s once symptoms are present, but researchers are hoping for more promising therapies in the future.

Our bodies, our minds

It’s easy to get in the weeds when trying to make a diagnosis. The symptoms are vast, and patients often ignore warning signs, brushing them off as age-related forgetfulness.

“There is no blood test. So what we recommend is that the primary care physician do a memory screen called the mini cog,” says Terrianne Reynolds, director of Medical and Research Activities with the Greater Illinois Chapter of the Alzheimer’s Association.

The mini cog is a three-part quick screen that can be performed during a routine doctor’s visit. It includes a clock drawing test, word registration and word recall. Though it may seem rudimentary when hunting for something as dangerous as a brain killer, the mini cog test can give doctors a cue to further assess a patient’s abilities.

An early diagnosis is important, Reynolds says. The sooner patients are diagnosed, the sooner they can enroll in research studies and make adjustments to their lifestyle, which may help stave off the disease.

A future to remember

With early diagnosis and early preventative measures in place, it’s easy to get excited and think that the end of Alzheimer’s is nigh. But that’s not the case. Between today and 2025, every state in the United States can expect a rise of at least 14 percent of people 65 and older with Alzheimer’s, according to the Alzheimer’s Association. Illinois is on the low end with an increase of 18.2 percent. Alaska is highest with 61.8 percent, followed by Nevada at 56.1 percent.

But future generations may see a better day and remember it, too. Because awareness will be better, and treatment will be better. In the meantime, there may be a small silver lining: “Patients are living longer. Instead of getting it at 75, you get it at 90,” Caserta says. “It’s a better life.”

Through NorthShore’s Center for Brain Health, Buchband took a genetic test that assessed her risks for Alzheimer’s and showed that she inherited some of her father’s protective genes. However, because she is female, she is still at greater risk for developing the disease. Both Buchband and her mother are doing their part to stave off Alzheimer’s. Both women work out and have improved their eating habits. Because t

he one thing that is certain is that exercise, a balanced diet, specifically the Mediterranean diet, and social engagement are powerful weapons to prevent Alzheimer’s.

“Nothing is impossible,” Maraganore says. “When healthcare and society commit to doing something important, we’ll see the change. Smoking is an example. We’re on the verge of the first smoke-free generation. We’ll succeed in changing the Alzheimer’s paradigm: from brain disorder to brain health.”