Adaptive approaches help address high obesity rates

While obesity is one of the biggest health concerns in many communities, people with disabilities suffer from obesity more than their peers. Because of physical limitations, they can find it more difficult to eat healthy, control their weight and be physically active. This can start a vicious cycle, and the weight gain can then cause additional health burdens, such as diabetes, heart disease and cancer.

Obesity rates for adults with disabilities are almost 60 percent higher than for adults without disabilities, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

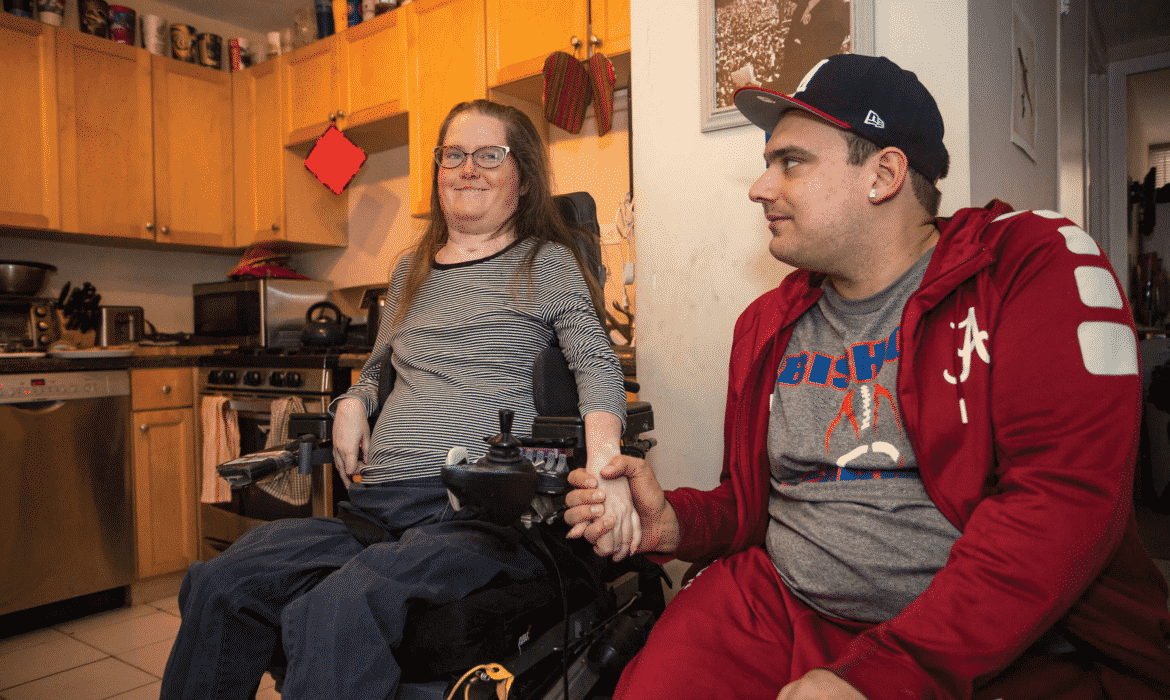

The statistics are not surprising to Chicagoan Rebecca Anger, who is living with quadriplegia in Chicago along with her husband Greg, who has cerebral palsy and uses a wheelchair. With physical and financial challenges, maintaining a healthy weight is hard but doable.

Rebecca, 33, currently does not have access to an exercise program. “I used to get physical therapy in primary and secondary school, but it is not covered by my insurance as an adult and it is extremely expensive,” she says.

Growing up and out

When children with disabilities are growing up, they may be cared for by family members who can look out for them, buy them a gym membership, drive them to physical therapy, take them to doctor appointments, prepare healthy meals and make sure they are eating well.

But when they live on their own, the challenges can increase both financially and physically. People with disabilities may have physical, hearing, visual or cognitive disabilities that prohibit access to a healthy lifestyle. They may also be on a limited budget due to high medical costs and unemployment.

Transportation to adaptive recreation and gyms is often an issue, and not all fitness centers have wheelchair-accessible exercise equipment. Individuals may need a physical therapist to modify exercises for them. Also, they may have difficulty preparing healthy meals in their own kitchen, which may not be wheelchair accessible.

Yet, despite these challenges, people like Rebecca and Greg Anger do their best to stay healthy and keep obesity at bay.

Nutrition matters

Proper nutrition is key for weight management, says Mary Frost, clinical nutrition manager at Northwestern Medicine’s Marianjoy Rehabilitation Hospital in Wheaton. People with disabilities may need 10 to 15 percent fewer calories than able-bodied adults, she says, because they have lower energy expenditures and lower levels of spontaneous activity due to their limited mobility.

But they may not have easy access to healthy and nutritious foods. Eating convenience foods and takeout may be quicker and easier than preparing food at home, but these foods are often high in fat and sodium, with large portion sizes.

“We are living in a land of portion distortion,” Frost says. “When I grew up in the 1960s, our meals were a quarter of the size they are now.” Dinner plates should consist of half fruits and vegetables, a quarter whole grains and a quarter protein, Frost says. “This is not a diet and it is not a quick fix. This is a lifestyle change.” To make it stick, she says, healthy eating has to become a way of life.

Frost provides patients with individualized nutrition plans to suit their needs. She strongly suggests that people struggling with weight management find a registered dietitian for help.

While it can be a challenge to make and eat healthy meals on a limited budget and with limited mobility, Rebecca says she can successfully manage her family’s diet.

Planning ahead makes it easier for her to make nourishing meals with whole foods. Because of their restrictions, Rebecca and Greg get creative with kitchen gadgets and tools. And Rebecca depends on a personal assistant to help her shop, cook and eat.

They cook most meals from scratch because it is healthier and more economical to eat at home than to eat out. “It is easy to buy fruits and vegetables on our budget if I buy everything on sale and in bulk,” she says. “We double recipes and freeze leftovers for future meals.”

“Eating well gives me the energy to live my life, which can be a challenge,” she says. “When I don’t eat my fruits and vegetables, I pay for it.”

Finding a passion for fitness

Greg, who is a substitute teacher for Chicago Public Schools, stays active to maintain his health. Until recently, keeping fit had been easy for Greg, who played recreational and competitive wheelchair basketball most of his life. He started at age 5 and continued with competitive ball through high school, college and grad school. He also played for the USA in the 2009 Australian Paralympic Youth Games.

Now that Greg, 28, is a busy, working newlywed, he doesn’t have time to commit to a competitive wheelchair basketball team. He still tries to find his passion to stay fit, though. With his cerebral palsy, he is able to bear weight and use a walker, though he usually uses a wheelchair to get around.

“I switch up my workouts to keep it interesting,” he says. “Sometimes I’ll walk on the treadmill in our apartment building gym for 30 minutes or lift weights.” He also recently purchased a wheelchair hand bike attachment to use on the lakefront path.

Educating the disability community on accessible activities and exercise programs is important, Greg says. Local YMCAs often have adaptive programs, and healthcare facilities may have adaptive fitness groups and personal training for people with disabilities.

Keeping in shape is essential. “Playing basketball all my life made me strong,” Greg says. “It’s important to maintain my strength so we can continue to live independently.”

Adaptive activities

Ricardo Lara, an exercise physiologist at Shirley Ryan AbilityLab, says that patients with disabilities need to find activities they love so they can stay fit and active. “It’s about finding activities they enjoy, modifying them and keeping consistently active,” he says.

It’s easier now that accessible equipment is more readily available than in the past. “Many manufacturers saw the need for accessible equipment and made an effort to provide it,” Lara says. All of the upper body equipment at Shirley Ryan AbilityLab can be used without having to transfer out of a wheelchair.

Patients can work out on the MOTOmed, a movement therapy system for arms and legs. “The MOTOmed allows individuals with limited or no use of their extremities to work out by using two built-in motors,” Lara says. “For those with some function, it allows them to work out for as long as they can and then allow the motor to continue working their muscles, resulting in increased blood flow and, in many cases, reduced spasms.”

Countering barriers

There are a multitude of barriers to nutrition and physical fitness for people with disabilities. The key to helping is to know what people’s internal and external barriers are and address them, says Sara Padalik, DO, a physiatrist with Northwestern Medicine’s Marianjoy Rehabilitation Hospital.

Getting out of the house and into the community can help. “Social engagement can be lacking for people with disabilities because it is easier to sit in front of the computer than it is to get out of the house,” Padalik says.

Living in an accessible city helps the Angers get out into the neighborhood, travel to the grocery store, access recreation and live independently. “The great thing about Chicago is that the trains and buses are accessible,” Greg says. For taxis, opentaxis.com, a centralized disability taxi dispatch, is helpful, he says.

Exercise and good nutrition is readily available to help individuals with disabilities keep fit and counter obesity. They just need to know the options are available.

“We need to spread the word and get people with disabilities active and out into their communities,” Padalik says. “There are options and there are resources. Let’s work together on it, not just individually, but as a community.”